“Artists you know as friends and heroes and teachers die, you miss their company, and what compensation there is, large enough to matter, arrives in the form of a wider, deeper — larger than life, one would almost venture to say — sense of their work, what it amounts to, where they took it, and how increasingly distinct as well as necessary it feels to be.”

— Bill Berkson, Sudden Address

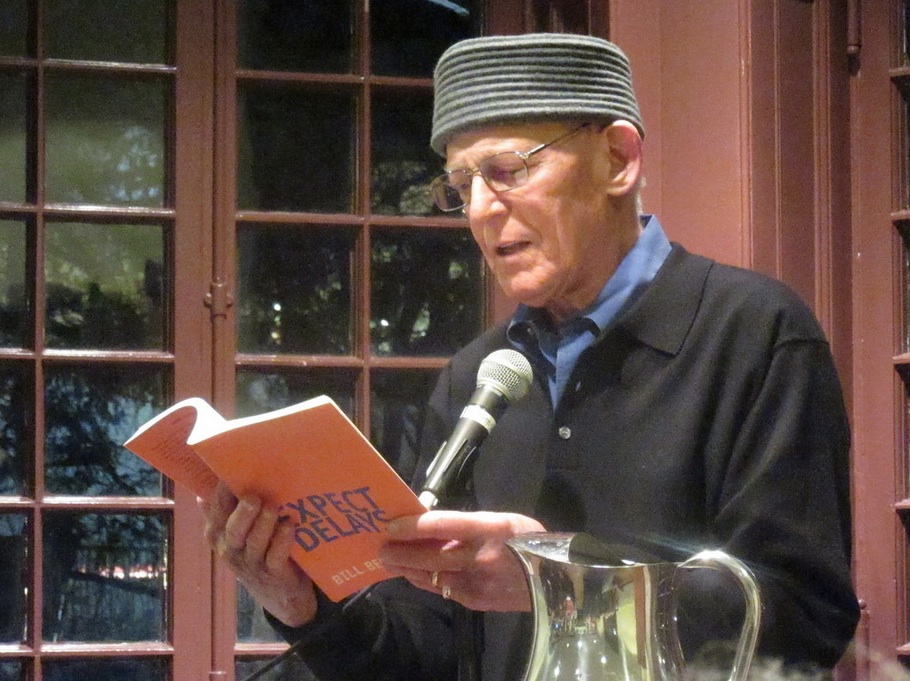

Bill Berkson, who died last week at age 76, was my professor in 2006 during his second-to-last year of teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute. Somewhere along the way, we became friends.

I have feared his appraisal, and I have been held in his regard. Both were intimidating and intoxicating in their forthright delivery. I have a picture of the two of us dancing, arms aloft as he spins me out into space, his bon vivant grace transferred to me for one brief moment. “Essence is distinct but inarticulate,” Bill wrote in his essay “Critical Reflections,” but with his death, memories have started to become fixed points forming the edges of our relationship. Grief is antithetical to the ambiguity and opacity of his poetry, but not to its intimacy. Each takes its own shape.

I have surrounded myself with his words in recent days, although in truth, they are always close at hand. There are five, six, no, seven volumes of his writing on my shelf, each a souvenir from listening to him read in classrooms, in bookstores, in galleries, for friends and strangers. Their title pages are inscribed with his shorthand dedications: “For Patricia, ‘with Heaven always in mind’ for you, Bill (p. 31)” graces the inside cover of The Sweet Singer of Modernism, a collection of his art writing and writing about art.

He was poet who wrote criticism and railed against the hyper-professionalism of both fields. He advocated for close and long encounters with works of art as an impetus to write as well as a subject for writing. “You can do a lot with educated eyes,” Bill wrote in the Sudden Address essay “Poetry and Painting.” And in the same paragraph, “At a certain point, past the shock of actually seeing, you want to do something about it.”

On Sunday, I went to the museum to look at a painting and think about Bill. SFMOMA’s second floor pays unintended tribute to his essays on the paintings of Joan Mitchell, Franz Kline, David Ireland, Robert Bechtle, David Parks, among others. Their works are all there, including Philip Guston’s For M (1955). Bill and Guston were good friends — he saw kinship in their mutually slow, accumulative processes — but I needed the scaffolding of bodies anchored in space. I settled before Parks’ Two Bathers (1958) with its spine and shoulder sculpted from pale teal, a cocked curved wrist of muddy ochre and a shroud of white towel enveloping a low, full belly swathed in midnight blue.

Bill wrote of this work in “Finding Eden,” saying that, “You feel as if they are strangers to the scenery, and to us, and they remain so.” He liked the inscrutability of paintings, the “chaos of impressions, blanks, needs, memories, obfuscations, and intermittent facts” with which art challenged language and rendered it woefully inadequate. The distance between the thing seen and the thing said could only be bridged by a reader. Bill taught me to think about whom that might be.