“Retard class” is not bad. I have a nice teacher, and every day we repeat the same mantras: “Columbus sailed the ocean blue….” And it is almost not horrible that a girl who has been reading since she was four and writing stories since she was five is in a class where no one knows how to read.

Because when I am in homeroom, I never know what horrors I will witness at the hands of Mrs. Stringer. Who will she make cry today? When she walks down the linoleum aisles for random desk checks, and your desk is not “clean,” she flips over your desk, and — in front of a classroom of children — you must pick up every paper, every pencil, and every crayon splayed across the floor, and put it neatly back in your desk.

You must be neat. You must be humble. You must be good.

I was not neat. I was not submissive. I was not her version of good.

Watching Diamanda Galás, I am not Michelle who is small and embarrassed. “Are you scared, Booski?” my dad says to me from the couch.

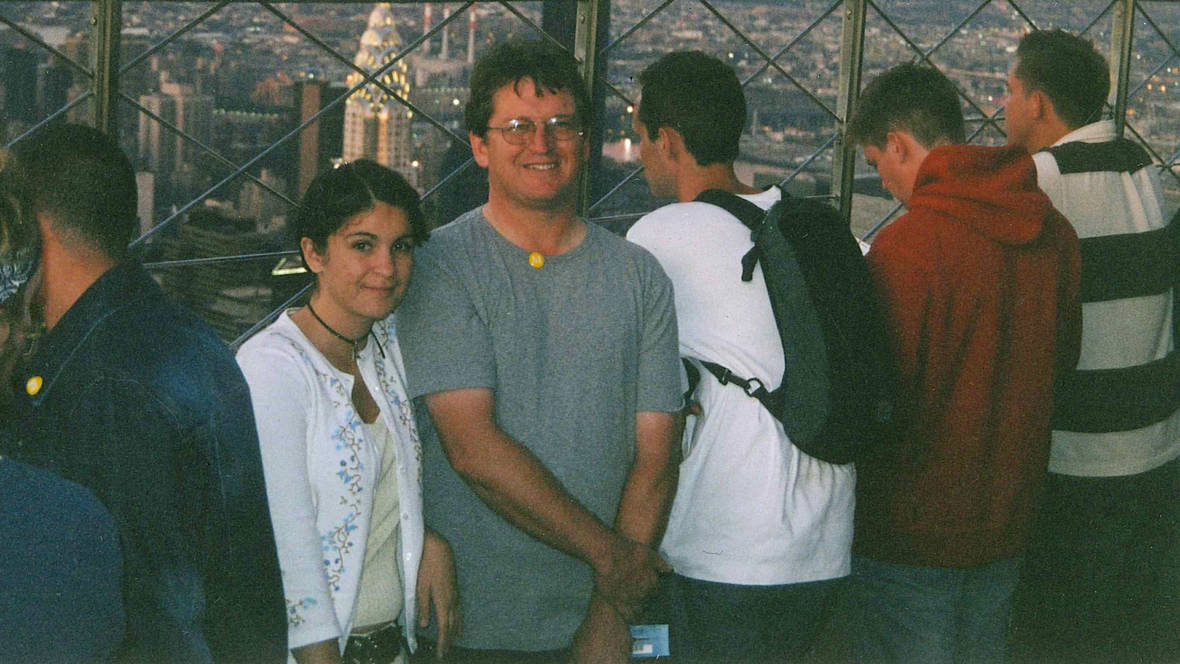

I am not sure when my Dad started calling me Boo, and its every incarnation: Booski, Booski Chillin, Boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-boo. Boo is not a pet name, but it’s a way for my Dad to say: I see you, and I care. I unfold myself off the floor, and walk over to the couch and drape myself across his lap.

“No, I like it,” I say, my eyes still on Diamanda. “I wish she could meet Mrs. Stringer.”

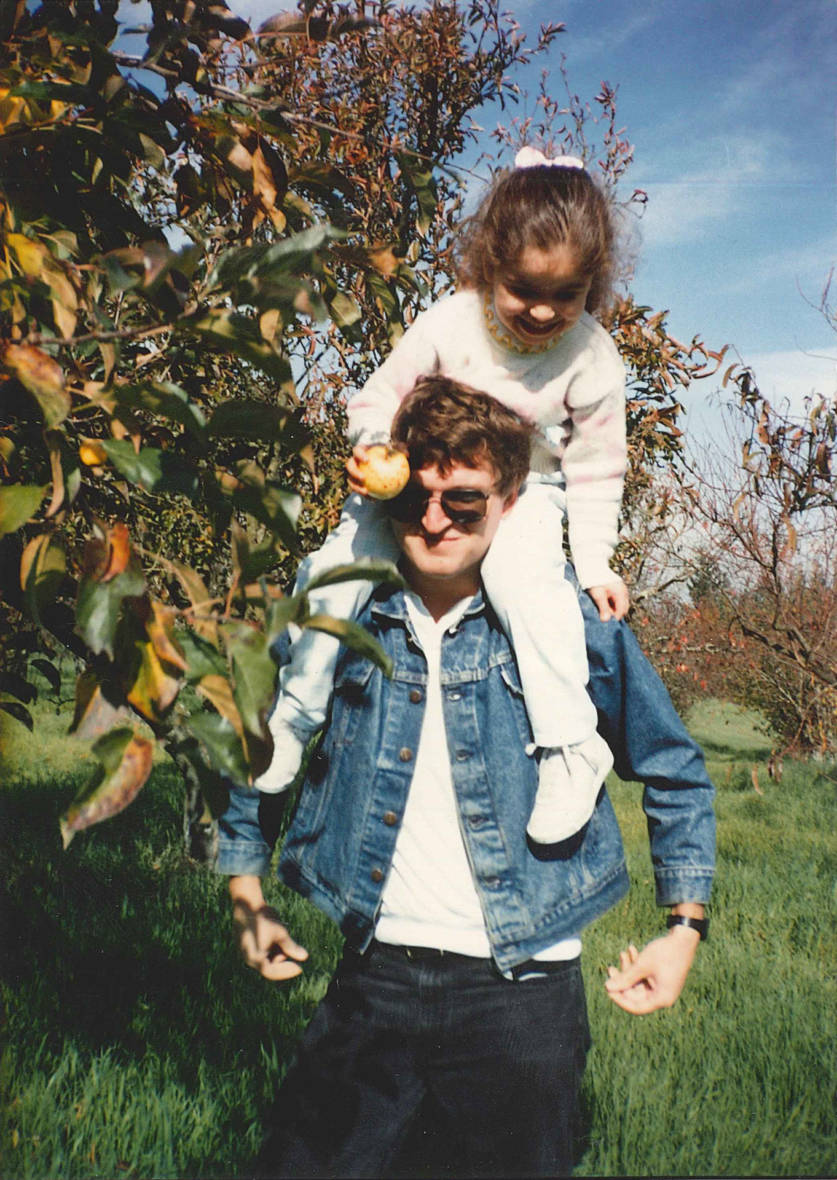

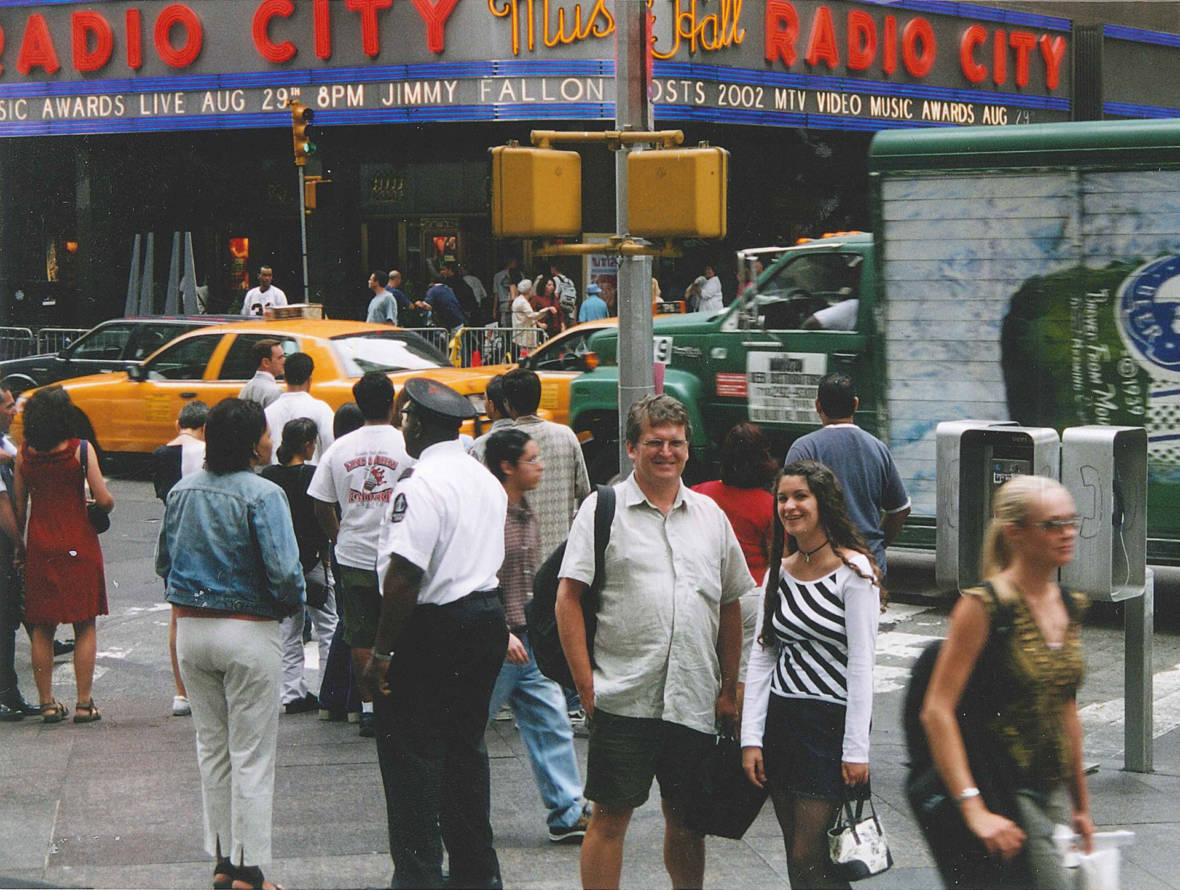

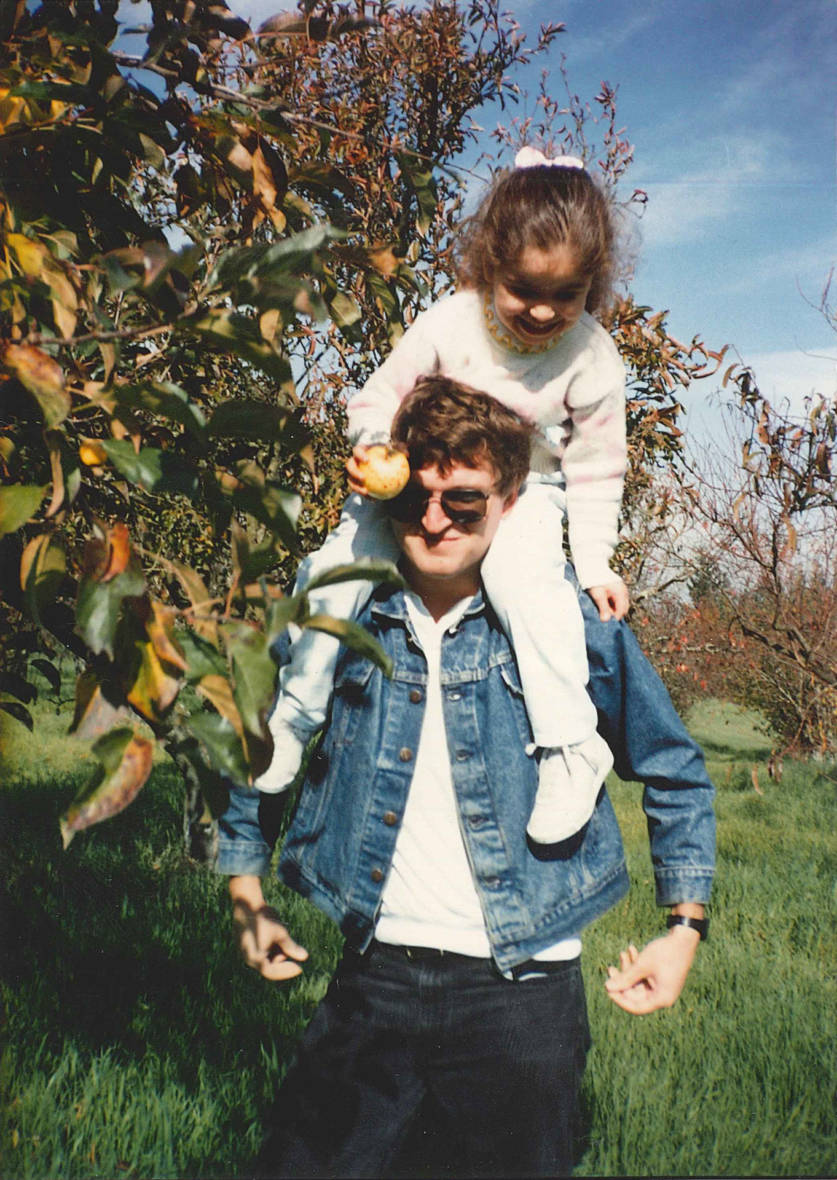

I am eight, and on my dad’s days off, we have a ritual: we go to Golden Gate Park, and we go to record stores.

I can usually convince my dad to go to the park first, so he can spend all the hours he wants later at Amoeba Music in Berkeley “looking at empty boxes,” as my mom would say. At the park, we climb the jungle gym together; I go on the slide and the swings. But that’s not the best part.

The best part is the pink popcorn, the cherry slushy, and the carousel that awaits in the distance. I think about that pink popcorn all week, until my dad is off work and I get to eat its sticky-chewy-sweetness while going around and around on the carousel. This is my heaven. After pink popcorn and cherry slushies, I am ready to go to Amoeba, where I will find bizarre ways to entertain myself.

My dad has never listened to “normal” music. He grew up playing in a prog-rock band in Denver called Anatomically Correct, and seeks out avant-jazz music with spiritual conviction. When I say “avant-jazz,” I don’t mean Ornette Coleman or Charles Mingus or anyone you’ve probably heard of. I mean the weirdest shit you’ve never heard: artists playing the inside of pianos, composers throwing balls across the floor, a twenty-piece orchestra improvising a thirty-minute song.

My dad has a different ear — you might say I inherited it.

At Amoeba, my dad is in the jazz section, while I am everywhere. I pinball from listening station to listening station, one minute listening to grunge, another minute to Mariah Carey. I sing and dance along by myself in the aisles, while other times I get lost in the kid’s video section. After it feels like his two hours are up, I stack my favorite videos in my arms and run over to my dad to negotiate how many videos he will buy for me.

I am more or less successful.

After we check out, we make our way to get pizza and Ben and Jerry’s. We both have a sweet tooth.

“When I was a teenage whore

My mother asked me, she said, “Baby, what for?

I give you plenty, why do you want more?

Baby, why are you a teenage whore?”

—Hole, “Teenage Whore,” Pretty on the Inside

The first time I am called a whore, I am 11 years old. I am thrown regularly into walls, against handball courts, onto pavement — whatever is closest and most available. I am the tallest girl in my class, but it feels like I can never make myself small enough.

Whore is my classmates’ insult of choice. I start eating all of my lunches alone in the school library, where I devour books like The Secret Garden, A Little Princess, and the entire Wizard of Oz series. After a few months in the library, I have read all the books I want to read, and I start bringing my own.

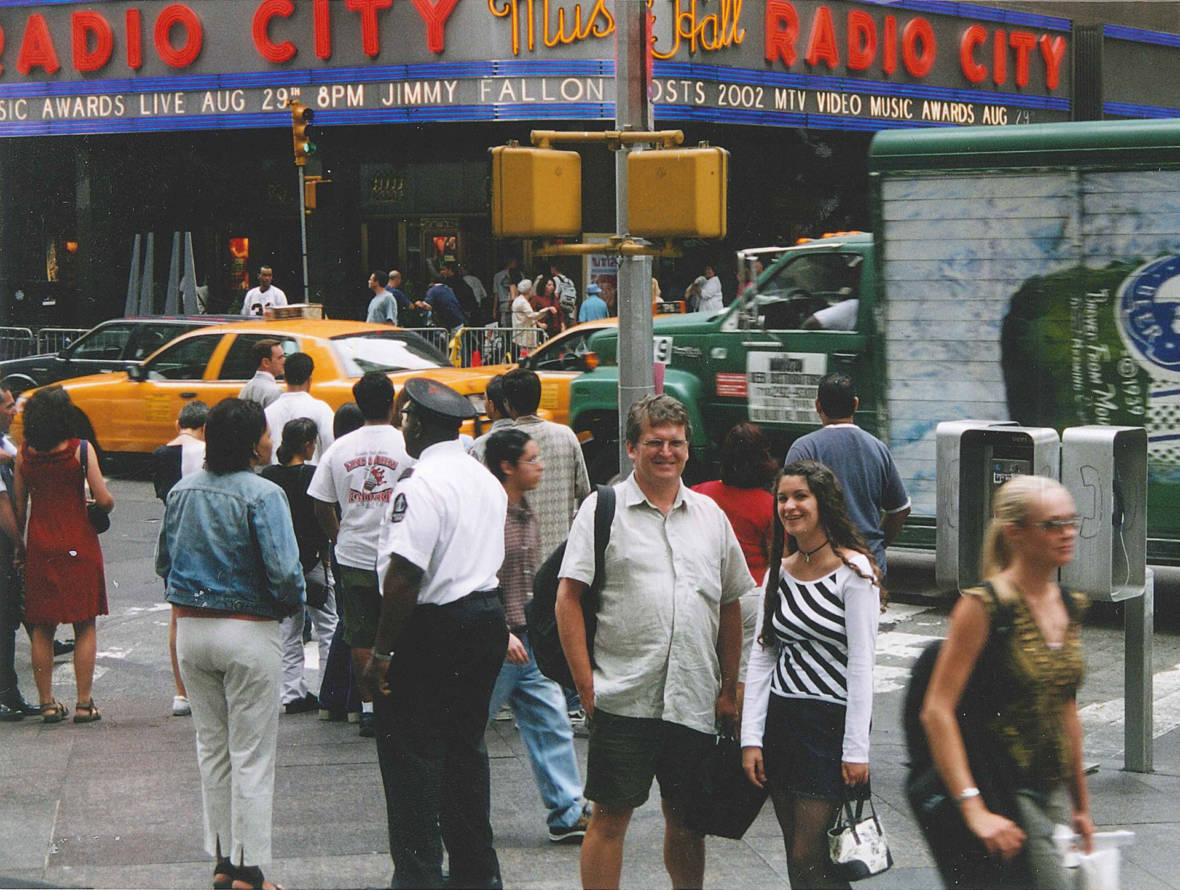

At Cody’s Books in Berkeley, while my dad shops at Amoeba, I drift from the kids’ section to the music section, where Poppy Z. Brite’s Courtney Love: The Real Story is on display. All I know about Courtney Love is that she once threw a makeup compact at Madonna. I pick up the book anyway.

In her biography, I learn about Love’s messy childhood. She was unloved. She went to boarding school. Later, while working as a stripper in Asia, her passport was confiscated and she was almost forced into prostitution. She went through drug addiction, had her child taken away from her, and endured most forms of emotional trauma possible.

I need this exact story, I think to myself. I need to believe that there’s a way out for angry, creative, weird girls. Later, I ask my Dad to buy Hole’s Celebrity Skin and Live Through This, and when we listen to the CDs in his car, it’s the first time my dad praises my musical taste.

Listening to Live Through This, I start to finally believe that I, too, can live through this. I watch all of Hole’s music videos, and I realize that Courtney Love is ugly in a beautiful way. I feel that way too. And so I decide I want to be Courtney Love. I buy babydoll dresses and wear purple lipstick and paint my nails black and wear plastic platform shoes. I start writing lyrics, and practicing songs that I write in my room. I develop a sick sense of humor. I get out of my skin.

When I get called whore at school, I start to laugh in response. In class, I write horror stories about what happens to bullies when they torture people. In front of the entire class, I read a story about a girl bullied by four boys, and how they all go on a field trip to a magical amusement park called Karma. The boys get on a Ferris wheel which ends up decapitating them all, while the girl rides the same Ferris wheel and nothing happens to her. The end.

I think I would have gotten kicked out of school had I written that same story today.

I wasn’t.

Instead, the kids became afraid of me. They stopped calling me whore.

I am 16, and working on a punk rock documentary and looking for source material.

“You should check out the old magazines that I have in the garage,” my dad tells me.

“Why would I ever want to read anything about jazz music?” I snark back.

“They’re zines I collected in the ’70s to ’90s. There’s a lot of punk stuff in there,” my Dad says.

Sure enough, in the garage are crates of old punk zines. Some with the Slits, the Raincoats, Bikini Kill and L7 on the cover. I get introduced to the Bad Brains, Agnostic Front, and T.S.O.L.

My dad looks through his old mixtapes and records for the bands that I like. And then he sneaks in a few that have nothing to do with punk. Laurie Anderson. Fela Kuti. The Residents.

I love it all. My weird ear further evolves. My dad has taught me to be sonically curious; to seek out music that needs to be digged out and dusted off to be appreciated.

He has taught me how to develop my own taste.

I am 29, crying on a bench in Berkeley, sitting next to my parents on my birthday. I’ve just found out that I’ve been rejected from a position as a music editor, the same week that I receive rejection letters from a literary fellowship and a writer’s residency.

Why am I doing this anymore?

“It’s okay, Booski,” my dad says to me, and I walk away because I don’t believe it, and if I respond I will claw his face with my words, and I already feel so self-indulgent and pathetic that I don’t need to feel guilty too.

I begin to micromanage my sentences. I start essays and stop mid-story. I quit writing.

But then, a devil woman saves me.

I get my first longform writing assignment in five years, on the musician Holly Herndon. She makes avant-garde electronic music, using her voice and computer as her primary instruments. She writes love letters to whomever is spying on her from the NSA, and collaborates with a group of radical programmers and musicians who, like herself, support Edward Snowden, create ‘caring critiques’ of the 1% and challenge Techtopia.

When I interview her, she pushes back gently on the stupidity of some of my questions. I ask her what it’s like to work with her partner and producer Mat Dryhurst, and she says “co-producer,” reminding me how often women are stripped of credit for producing their own work. I try to discuss other women in electronic music that have influenced her, and she informs me that “women in music” isn’t a genre. In her responses, she challenges me to be a better writer.

I interview her teachers and artistic collaborators, and I remember how much I miss reporting. When I sit down to write my feature, it is difficult, not because the writing itself is hard, but because I have so much to say.

Holly has given me back my voice.

At her concert at the Chapel, she is the first artist I’ve seen who truly makes music an experience. The room shakes, the video installation work of artists Metahaven and Akihiko Taniguchi drifts across her face, and as she pauses between sets, she uses her computer to communicate with the audience, typing sweet and salty messages to us on the screen. Holly has said that the computer is the “most intimate instrument,” that it knows us, that it filters our experiences.

My dad would love this show.

Later, I call my dad to tell him about the perfectly pointed weirdness of it all. “I wish I was there,” he says.

I wish he was there too. He was the only thing missing.