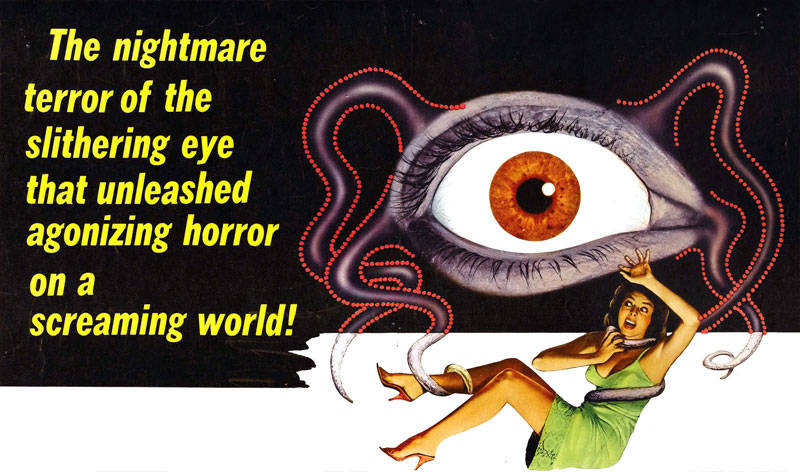

I live by the beach, and we know that summer begins when the sun disappears towards the end of May, for about three months. That’s when it becomes the land of The Crawling Eye, a z-budget movie from 1958 about a giant alien eyeball that crash lands in the Swiss alps and is accompanied by a fog bank as it crawls about, decapitating unsuspecting Swiss people.

I live by the beach, and we know that summer begins when the sun disappears towards the end of May, for about three months. That’s when it becomes the land of The Crawling Eye, a z-budget movie from 1958 about a giant alien eyeball that crash lands in the Swiss alps and is accompanied by a fog bank as it crawls about, decapitating unsuspecting Swiss people.

When the fog rolls in, there’s no better time to kick back in your cozy living room and read some really weird books. This year has seen an assortment of titles published that would give H.P. Lovecraft the chills and if that’s your scene, I suggest pulling up a giant alien eyeball and checking out any of the strange tales below.

The Loney

by Andrew Michael Hurley

We’ll start with The Loney, a dark gothic novel set along “the loney,” a part of the English coast that might have hosted our all-seeing friend. Cold, windy, muddy, edged with dank scraps of dense, unfriendly vegetation, it’s just the place to take your family on an annual basis for an unpleasant and perhaps unholy Easter celebration. Smith, who tries to tell the story, but is prone to wind back and forth in his memory, recalls, as best he can, his brother Hanny, a mute whom his dangerously-devout mother hoped to cure with sinister rituals. There was a child’s body washed up in the mud and thorns that lined the shore. Did something fantastic intrude into these grim everyday lives, or were those lives simply worse than we care to imagine? Hurley’s powerful prose and his intense sense of place and character bring to mind the best that the Gothic fiction genre has to offer. Read it before booking that cottage on the coast.

The Assistants

by Camille Perri

Camille Perri’s debut novel, The Assistants, is narrated by Tina Fontana, assistant to a billionaire media mogul who pays for an hors d’oeuvre what she pays in rent for her tiny apartment. The luxury gap is alive and well, and Tina is staring at a student loan debt of $20,000. Circumstances offer her an exit that she takes with the tiniest moral pivot, but one step away from the straight and narrow leads to another step and another debt-riddled ex-student. As Tina takes us down a rabbit-hole of cascading consequences, Perri crafts a novel that offers a charming look at friendship, courtship and corporate shenanigans in the early 21st century. You may guess where all this is going — a scheme, perhaps? — but not how far. And having Tina as your guide is the kind of bonus that even a benevolent corporation can’t offer. She’s witty and gritty, with a perfectly honed predilection for salty language that brings on the laughs. You may read it in a day or two, but it will play in your brain for much longer than that. There are a lot of ways to break the glass ceiling; some may involve breaking, or at least bending the law.

The Race

by Nina Allan

On the other side of the debut universe, or more likely in one adjacent to ours, you can find Nina Allan’s remarkable The Race. In admirably direct prose, we meet Jenna Hoolman, who tells us about her life in Sapphire in a devastated future. The only game in town is smartdog racing, which involves humans bonded to dogs. “There’s a lot of hard-science stuff I don’t understand fully,” Jenna tells us. In fact the future itself seems a bit blurry, until Allan snaps it into crystal clear focus. Our narrator may not be who we think she is. And the smartdog-runner relationship may prove to have parallels even the most literary aficionados may not suspect. Rest assured this is not the science fiction you thought you were buying, but something even stranger and more powerful. Stories unfold within stories, fiction begets even stranger fictions set in more familiar places. Here’s the good news: the best means of gaining any perspective requires one to step away from the object you are trying to understand. It’s essential to preserve the mysteries at the heart of this astonishing novel. But as Nina Allan whipsaws your mind from this world to the next and back to this one, upon your return to wherever you were when you started The Race, you will realize that perspective cuts two ways. Try as you might, you can’t unsee the truth.

Muladona

by Eric Stener Carlson

Tartarus Press is a specialty publisher from the moors of Britain with a focus on the supernatural and the weird. They were the original publisher of Andrew Michael Hurley’s The Loney, before it started winning prizes and acclaim. Eric Stener Carlson’s Muladona unfolds in 1918, as the Spanish flu kills off the residents of Incarnation, Texas. Verge Strömberg is a bookworm and the son of an overbearing town pastor, who leaves him behind to tend church elsewhere. That’s when the Muladona begins coming to him – a fire-breathing winged mule from hell (and Mexican folklore). It begins to tell him stories, taunting him in true supernatural fashion to guess its name. It’s an upside-down, supernatural Scheherazade, with a hardscrabble, western-dirt feel. Carlson captures the terror of an almost-remembered nightmare, juxtaposing the familiar and the strange with ease. While Tartarus hails from the darkest moors of Britain, Muladona speaks the black heart of American greed.

The Heavenly Table

by Donald Ray Pollack

Donald Ray Pollack’s The Heavenly Table is not a cookbook, but it is every bit as disturbing as the tome To Serve Man in the famous Damon Knight story adapted by Rod Serling for The Twilight Zone. It’s 1917, the 20th century is finally coming into focus, and it is not a happy sight. Cane, Cob and Chimney Jewett lose everything and set off to kill, rob and pillage everything in their path, inspired by a dime novel that revels in blood. The Fiddlers, Ellsworth, Eula and their son Eddie, live hundreds of miles away from the Jewetts, but not far enough. Their paths will cross and it will not end well for Pollack’s characters, crafted from blood, steel and stone. We believe these people, and in them, even if they are despicable. There’s a point where despicable becomes easy — necessary even. Exciting and powerful, The Heavenly Table offers the visionary pleasures of Flannery O’Connor with a hefty dose of gun (and other) violence. Pollack humanizes his most desperately terrible characters, even if we wish he would not. The Heavenly Table is a serving of American literary ultra-violence that steps well beyond wild into weird.

The Last Days of New Paris

by China Miéville

Let’s just get to the heart of weird, with the man who invented a genre he called “the New Weird,” China Miéville. The Last Days of New Paris posits that in 1941, a surrealist bomb detonated in Nazi-occupied Paris. The horrific, disturbing, and yes, surreal images of those paintings were made real. In 1950, the war drags on and New Paris, as it is called, is under a new attack, as the Nazis have unsurprisingly made contact with Hell and managed to import demons to aid in their fight. Thibault is a soldier fighting for the surrealists, trying to keep track of the manifs, which is to say, those manifestations from the art. “Of those many manifs mentioned in the narrative, there are, I’m sure, many I’ve failed to identify. If I understand it correctly, it’s in the nature of the S-Blast that the great bulk of its results are random or manifest the work of unknown artists–by which in Surrealist fashion, I mean people.” So, yes, people are weird. The book is both illustrated and annotated. Miéville is consistently brilliant and weird in equal measure. This is clearly the best book about surrealist art brought to life to fight in WWII ever written.

Where the Time Goes

by Jeffrey E. Barlough

The potential in fantasy literature for the weird is great, but the realization is low. We can thank Jeffrey E. Barlough, then, for his utterly unique Western Lights novels. They all stand alone, though they partake of the same backdrop — a sort of Victorian London plopped down in the American West and mid-west, sans gunpowder, but with mastodons, wooly mammoths and giant sloths roaming the hills. The latest entry, Where the Time Goes finds Dr. Hugh Callender returning home to Dithering in the Lingonshire, to investigate the monster in Eldritch’s Cupboard, if indeed it even exists. The charm of Barlough’s work is that he writes as if he’s living in the world he has created with a lovely and enjoyably jolly faux-Victorian prose. He also loves his characters so much that you cannot help but feel the same. He creates real tension and when he dials up the creep factor, he can make your skin crawl with the merest suggestion. This is the ninth book in the series, so if you want to catch up while you wait for this one, there are plenty to read. Order is unimportant, but these books are an important reminder that the human imagination has no bounds. They also remind us that there is art in literature that simply cannot be experienced in any other way.