Behind the character of Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a line of thousands of actors. They have come to him over and over again, as if he were less a role to play than an artistic pilgrimage. We speak of Olivier’s Hamlet, Burton’s Hamlet, Gielgud’s Hamlet, Richardson’s, Berkoff’s, Kline’s, Hawkes’, Branagh’s, Cumberbatch’s…the list goes on. And we even speak with regret of the Hamlets that might have been: Brando’s, Dean’s, Welles’. We dream of them all, if only to toss them aside as likely to have come up short.

Yet Hamlet will have none of it. The most definitive character of the Western canon is also the most elusive. Every attempt seems a gloss — an approximation of the real thing. And so Shakespeare’s Hamlet has always seemed more of an actor’s play than a director’s; more about an ambitious actor confronting an impossible role than the personal and political struggles of one royal family in Denmark. As a weeping teenager said to me after a rather pedestrian production, “we have lost a beautiful soul.” One might add, that we have lost all the souls determined to bring that soul to life. Enter the graveyard and behold the ghosts. It’s a crowded field.

Mark Jackson knows that. The director and conceptual wizard behind the Shotgun Players’ uplifting and weirdly affecting Hamlet once performed a version of the play, I am Hamlet, in which Hamlet played all the roles himself.

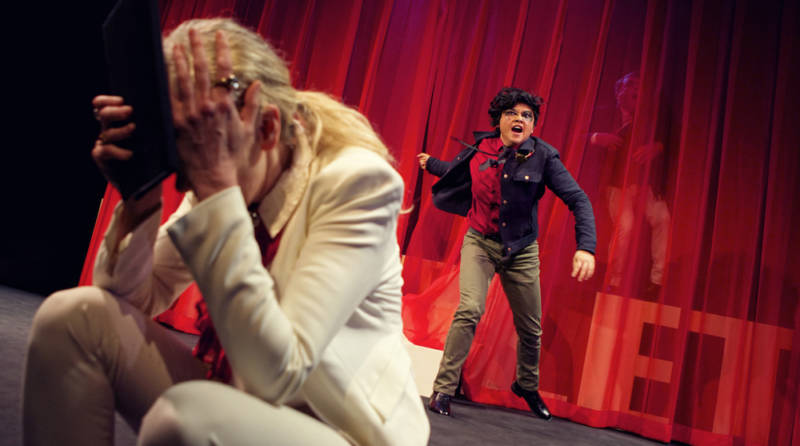

Here, Jackson reverses the equation. Announcing before the performance begins to the audience that the actors have no idea who they’re going to play — and in fact no one does, not even the director himself — he invites the cast of seven on stage. The actors run out with the peppy bonhomie of game show contestants, line up in a row before us, and wait. Who will play Hamlet? And for that matter Claudius, Ophelia, Polonius, Laertes? Jackson pulls the cast list out of Yorick’s skull and assigns the parts one by one. It’s a goofy, curiously intense moment.

You immediately notice that there isn’t a conventional Hamlet in the cast. They are a wonderfully eclectic bunch: men and women, a smattering of ages and races, and, if you follow Bay Area performers, even different acting styles. So the first move Jackson makes in this Hamlet is both to play up and side step the drama of playing Hamlet. There will be a confrontation between actor and role, but one unknown until the very last moment. And this is the rub: what is true for Hamlet will now be true for all the other roles as well. We are plunged into a democracy of infinite possibilities.