As an international star who forged a singular synthesis of jazz, funk, and the music of his township youth in South Africa, Hugh Masekela has received top billing at concert halls and theaters for nearly five decades. But when the trumpeter and vocalist arrives at the SFJAZZ Center for a three-night run starting Nov. 27, he shares the marquee lights with Larry Willis, a veteran New York jazz pianist, composer and arranger making his first Bay Area appearance under his own name (as opposed to dozens of gigs over the years as a sideman with the likes of drum legend Jimmy Cobb, trumpeter Roy Hargrove, and Jerry Gonzalez’s Fort Apache Band).

Willis and Masekela met and bonded in the early 1960s as students at the Manhattan School of Music, and their current piano-trumpet duo is just the latest manifestation of a fruitful and enduring friendship. Since releasing 2012’s Friends (House of Masekela), a wide-ranging four-disc album recorded in South Africa, they’ve toured together with shared billing, giving Willis an unprecedented turn in the spotlight.

For Masekela, 76, the project is all about “brotherhood, and how we get into the songs,” he says, by phone while traveling to a gig with Willis in Pennsylvania. “We love all kinds of music. We love beautiful songs, from Bach to Bob Dylan to Miriam Makeba, regardless of who sang it. Sometimes I think, that’s such a tired song, but if Larry likes a song he’ll make you like it.”

Masekela’s heroic story has been oft told (most vividly in his 2004 autobiography Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela). Initially inspired by bebop, he became a pop star with his chart-topping 1968 hit “Grazing In the Grass,” and has spent most of his subsequent years championing the music and culture of South Africa while collaborating with musicians from across the continent. Constantly in motion in the 1970s and ’80s, he absorbed new influences as quickly as his address changed, bouncing between Guinea, New York City, Los Angeles, Liberia, London, Ghana and Botswana — sometimes one step ahead of assassins working for South Africa’s apartheid government. His three decades of exile ended in 1990 when he returned to his homeland just weeks after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.

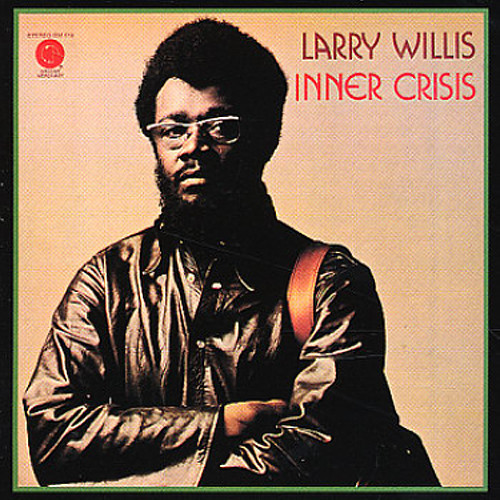

While Masekela grew up in a violent and hardscrabble township, Willis came of age in an upwardly mobile family in Harlem, suffused with music. In one of jazz’s most unexpected recording debuts, Willis first went into the studio as a vocalist featured on a Leonard Bernstein-conducted Columbia Masterworks recording of Aaron Copeland’s two-act opera The Second Hurricane. Though Willis still sings, Masekela handles most of the duo’s vocals (they harmonize on several traditional South African songs that Willis learned from Miriam Makeba). Willis, 72, was never that gung-ho about vocal studies, admitting that “it was the easiest way” into the Manhattan School of Music. “College was necessary to please my parents, but at the time I had little interest in being a musician at all,” he said. “I was more interested in athletics, playing varsity baseball and basketball.”