Editor’s Note: Bay Area Painting Right Now peers into the studios of emerging local painters to find out what they’re making, how they’re making it and why. Guiding our tour is Brandon Brown, poet, writer, editor and unabashed fan of contemporary painting. Don’t miss the first installment of this series on Lana Williams.

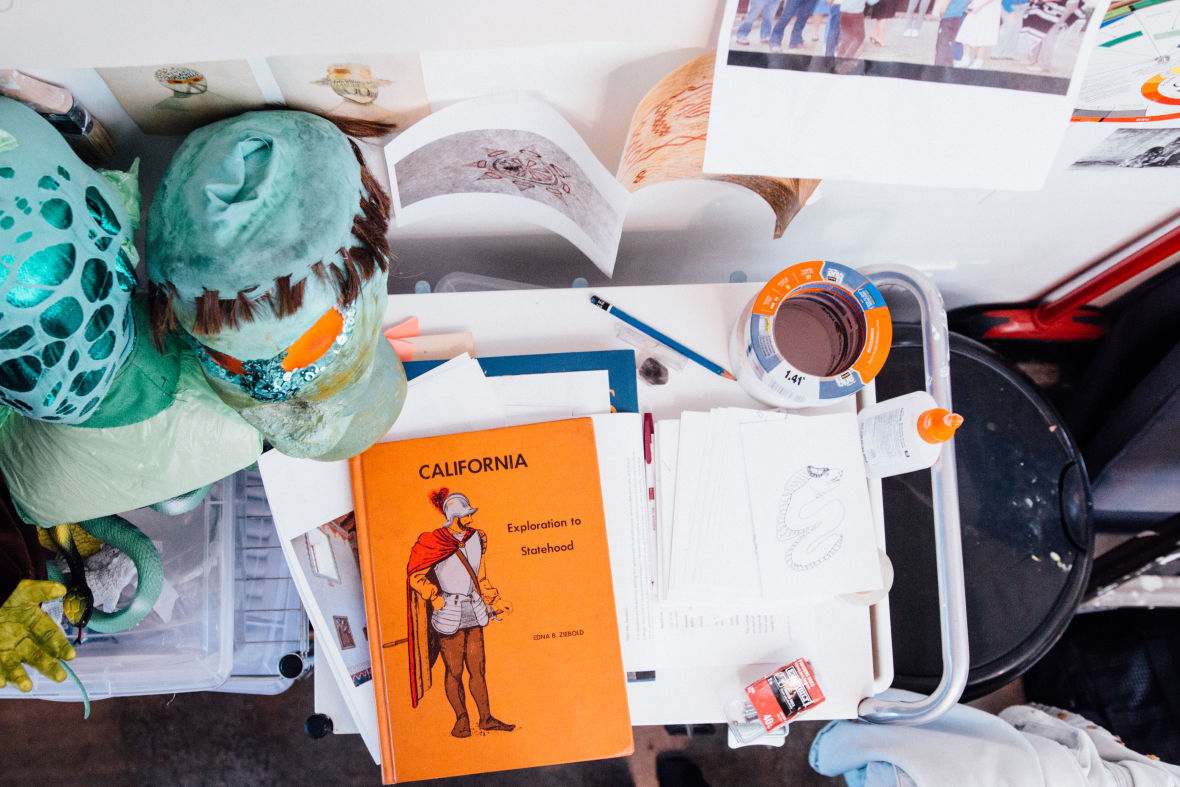

Katie Dorame paints in an ample structure in the yard behind her northwest Oakland home. Paintings and drawings line the right wall of the studio, while the left wall is covered by an eclectic bunch of materials: paint and supplies, frocked space aliens and tacked-up papers, including a still from Pee Wee’s Big Adventure.

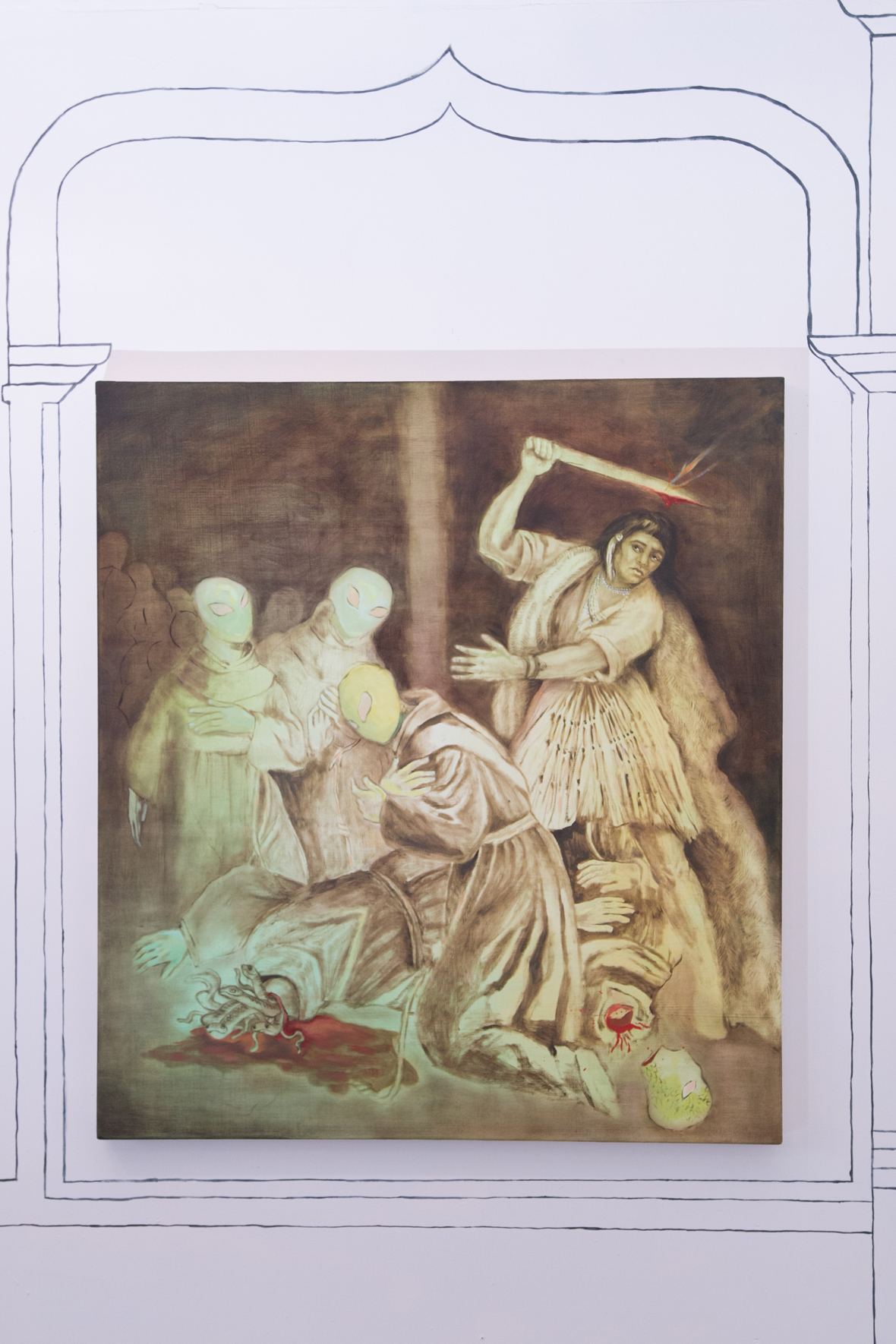

At the rear of the space, the atmosphere changes dramatically. It becomes less of a studio and more of a set. Two large oil paintings flank the back wall, suggesting the religious paintings one finds in Catholic churches. And indeed, designs painted on the wall around the canvases refer to a particular form of architecture — the California mission.

The Spanish built 21 missions in California between 1769 and 1833. They were religious and military outposts, administrative centers through which Spain waged a colonial effort to subjugate the indigenous people of California. Visiting them now is a strange and complex endeavor.

On one hand, the buildings are among the oldest surviving religious structures in California, inspiring writers like San Francisco’s Bruce Boone in his legendary My Walk With Bob and Alfred Hitchcock, who used Mission San Juan Batista in his film Vertigo. On the other hand, the missions are remnants of a centuries-long war against Native Americans. Every element of these buildings, from their foundations to decorative ornaments, is a relic of extreme violence.

Dorame’s interest in the missions is tied to the critical focus of her painting practice: narrative. As we discussed her growing interest in art as a teen, she described the moment she realized painting was a way for her to tell stories. In this way, Dorame’s extraordinary interpretations of the missions, California history and the artwork they’ve both appropriated and inspired, enter a long tradition of other interpretations about what the missions represent.