It’s summertime and that means the cineplex will be chock full of superheros and other big-budget fare. But if you’re someone who prefers to while away the months avoiding the hype and exploring some lesser-known titles, here’s an eclectic list of gloomy, back-catalogue films that probably have escaped your notice, and can serve as the perfect antidote for those who like their fun-in-the sun on the dark side.

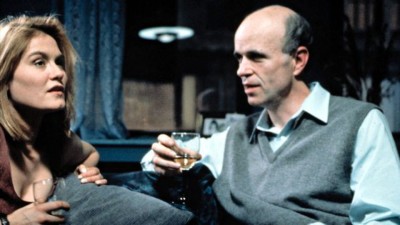

What Happened Was…

1994

Last year was the 20th anniversary of the greatest movie practically no one has seen. When I mentioned to What Happened Was … producer Ted Hope that I was fan of the film, his reaction was: “You saw it?” Part of the picture’s obscurity has to do with the fact that it’s never been released on DVD, despite having won the Grand Jury Prize and the screenwriting award at Sundance, and writer/director/star Tom Noonan’s one man tour-de-force of moviemaking is one of the great lost films of contemporary cinema.

The film has only two characters and takes place over the course of a single first date, all within the New York City apartment of Jackie (Karen Sillas), a 30-something administrative assistant at a law firm. Her partner in awkwardness is Michael (played by Noonan), an older, morose paralegal. The scenario gives off a whiff of studio rom-com, suggesting a conventionally kooky, opposites-attract time.

But what gives the film its edge, besides the spellbinding performances, is the destructive way these two recognizable types from any pool of office workers try to navigate the commonplace occurrence of an embarrassing first date. Alternately hilarious and horrifying, their clumsy attempts at normative behavior slowly reveal the kind of trauma many people carry to work along with their microwavable lunches. Noonan avoids the staginess you might typically find in a two-hander set in an apartment by using the camera and inventive blocking to open up the space so that it drips with latent despair. Subliminal sound and visual design add to the mix. And though it’s not available on DVD, you can find it on Amazon and iTunes.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baad Asssss Song

1971

Director Melvin Van Peebles said he made Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassss Song because he didn’t care much for the way movies portrayed African Americans. When asked later by an interviewer to name some of the films he took issue with, he said, “About every damn thing that had a black person in it.”

His film tells the story of a black man on the run from police. It’s most explosive component: the depiction of overt racism and brutality by the LAPD, an issue that has plagued the department and the community it polices for decades. In a typical sequence, cops brutally beat a black man in bed with a white woman. One of them realizes the man is not who they’re looking for. “That’s not him,” he says. “So what?” says his partner.

While the independently-made Sweetback is often credited with ushering in the “blaxploitation” genre, it has a much rawer quality than the Hollywood-made films that followed. And as far as style goes, you could call it impressionistic, off-the-wall… You could even call it a travesty. I’ve seen it four times and I still have a hard time figuring out what’s going on. Some audiences weaned on traditional film technique will find it utterly inaccessible, and you can’t always determine what is a piece of experimental brilliance and what is simply a mistake.

Yet, there is unmistakable greatness here, not the least of which is an all-time great jazz-funk score by newcomers Earth, Wind and Fire. This is an in-your-face look at institutional racism rarely seen at the movies. As we see Sweetback literally on the run, his flight becomes the central metaphor in a depiction of one man’s attempt to break free from violent racism. “No him, no me,” Dizzy Gillespie once said of Louis Armstrong. In the continuum of African American cinema, Sweet Sweetback’s Baad Asssss Song is at the forefront.

Images

1972

The great American movie director Robert Altman is best known for his 1992 film The Player, the 1970 box office smash M*A*S*H, and a spate of 1970s critical successes like Nashville. But one often overlooked Altman work of brilliance is Images. This is one of those Altman films in which he ditches his ensemble cast, multiple storyline approach and embroiders a tight, focused piece about a housewife experiencing a psychotic break.

Without cliche or fuss, Altman puts us right inside the head of the lead character, played by Susannah York, depicting her break with reality in an almost understated way. The tension derives from the audience not knowing what she has mistaken for real and what has truly occurred. Is she having sex with her husband or her husband’s friend? Or is it her dead lover, in an incident she has only imagined?

The film tinkers with traditional film grammar to mimic the disorienting, dreamlike continuum of action and images in the degenerating reality experienced by a disordered mind. Along the way, Altman manages to score direct hits on male behavior, subtly linking York’s breakdown with the boorishness of her husband and aggressive sexual harassment by his friend. With its haunted Irish countryside, moody Vilmos Zsigmond cinematography, and echoing, clattering, blaring cacophony of a soundtrack, Images has all the earmarks of a great horror film. Throw in the creepy voiceover of Susannah York reading a children’s story, and there will be chills.

Battle Royale

2000

A group of kids is sent to a deserted island to participate in an annual contest in which they are ordered to fight each other to the death, the last one standing winning the right to go home a hero. Sound familiar? While the basic concept describes The Hunger Games, the scenario was first used in Battle Royale, a 2000 Japanese movie based on a novel of the same name (later a manga series) and directed by Kinji Fukasaku. The film didn’t get a U..S. showing until a limited release in late 2011 and 2012.

The Hunger Games movie franchise may have reaped a billion dollars, but Battle Royale is a much more interesting work. Despite its grim conceit, the PG-13 violence in Hunger Games is sanitized, while in Battle Royale, all bets are off. When the captive class of junior-high age students is first told they have been chosen by lottery to participate in a contest to the death, one of the kids laughs at the preposterous notion. But when the contest facilitator casually pulls out the knife he has hurled into one girl’s forehead, pandemonium ensues — a chaos that mimics what’s occurring to your own sense of what’s acceptable in a movie. Like it or not, there is going to be no audience hand-holding here as this film means business.

What follows is a well-imagined story of how children might react given the circumstances. Some start killing each other immediately, others treat it as a problem to figure out, some go into denial, and two resist by committing suicide. Throughout, some of the kids can muster only a comical yet utterly realistic helplessness. (One boy asks a classmate with an ax stuck in his head, “You okay?”)

Some may find the whole thing inherently distasteful, but you have to marvel at the film’s audaciousness. There’s a deep commitment to the mayhem, and an extraordinary mingling of pubescent melodrama, and all its attendant tenderness of emotions, with breakneck action and vicious violence. It’s sort of like the last year of junior high — cliques, grudges, bullying, first-love — only with axes and machine guns. There’s a real poignancy that in the midst of the murderous turmoil, some kids still feel compelled to discuss who has a crush on who.

In 2009, Quentin Tarantino called Battle Royale the best film since he started directing in 1992. He said, “If there is any movie that has been made since I’ve been making movies that I wish I had made, it’s that one.” (Tarantino would later use Battle Royale’s Chiaki Kuriyama in his Kill Bill series.)

Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story

1987

Todd Haynes’ 44-minute film about Karen Carpenter’s losing battle with anorexia nervosa is an underground work in the truest sense. Haynes was unable to secure the rights to the Carpenters music he used throughout the film, and Richard Carpenter, the other half of the musical duo that made so many soft-pop hits in the 70s, threatened Haynes with legal action, citing copyright infringement. In the book Hollywood’s Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet, author Peter Decherney writes, “Superstar is a very rare instance from the 1980s and 1990s in which a work of experimental film and video has been suppressed by copyright law, even by a simple cease and desist letter.”

Before the era of online video, the film was shown only at festivals, though you may have been able to get your hands on an Illegal DVD copy. Now, though, you are free to watch it on YouTube and other video sites.

The most prominent thing about Superstar is that the story is told using dolls, an inherently creepy cinematic strategy. One interpretation when watching their lifeless, frozen expressions married to dubbed dialogue is that Haynes is critiquing what he sees as suburban vapidity and the suppression of reality beneath a plastic form. As the duo’s anodyne music plays, Haynes mixes in images of the Vietnam War and Nixon, and he includes a music critic opining that the Carpenters “epitomized for me the return to reactionary values in the 70s. I never trusted them.”

A combination of lurid biopic, cinematic lark, and bold experiment, the film never comes across as merely campy and disrespectful. Highly watchable despite its experimental bent, Superstar leaves you with a genuine sense of tragedy.

The Wife

1995

This is Tom Noonan’s follow-up to What Happened Was… Just watch the fun begin as a mismatched couple drop by the house of a pair of married, New Age therapists, creating total emotional havoc. Noonan plays a shrink without boundaries, wielding extreme passive aggressiveness during the world’s most excruciating dinner. As in What Happened, the writer/director excels at dramatizing states of barely warded-off despair, tapping into deep wellsprings of loneliness. Much of the drama lies in the reaction shots of the characters, ignoring or shooting knowing looks at one another other while someone else bloviates in absorbed monologue. As everyone get drunker, the stakes are upped, and despite the verbiage, the inability to connect is profound. While The Wife has its share of self-indulgent directorial elements, the anguish depicted is almost Bergmanesque.

The film was nominated for a Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 1995. But Noonan’s made only two films since. “It’s disappointing to me I haven’t done more,” he told me last year. “I did What Happened Was… and The Wife, and I thought I’ll be doing this for the next 30 years — I’ll be like Woody allen, I’ll make 50 movies.” Still, he’s not totally unappreciated. Cinema polemicist and Boston University film and American studies professor Ray Carney calls Noonan the “greatest living American director.”