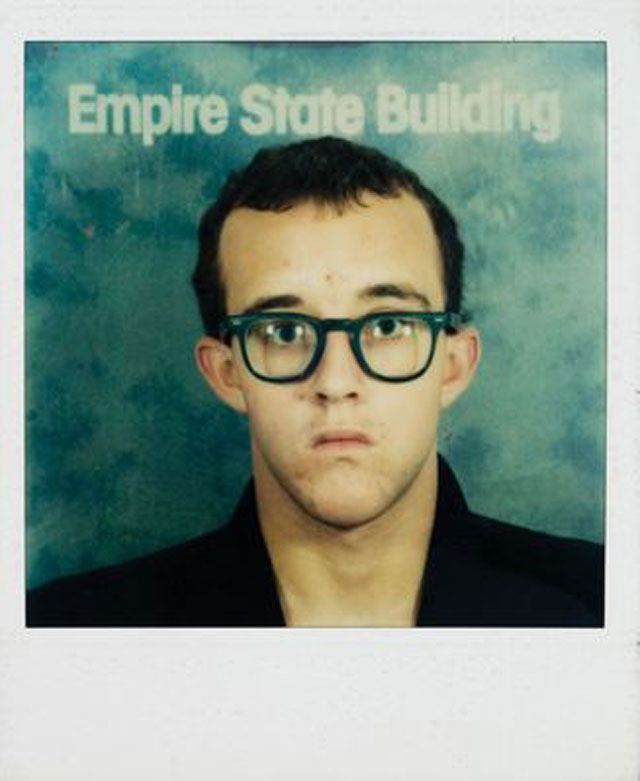

In the late 1980s Keith Haring’s work was ubiquitous to the point of being overwhelming. The fact that his style was widely ripped off only seemed to extend his reach. Haring-esque dancing figures and crawling babies were everywhere, populating the world with squiggly lines detached from meaning; personally, I couldn’t stand it at the time. Keith Haring: The Political Line at the de Young will radically recalibrate the artist’s work for late converts like myself.

Though the artist has been gone nearly twenty-five years — he passed away in 1990, just shy of age 32, from AIDS-related complications — the cogent politics in his work are reborn with great vigor in this extensive survey. Seeing his work now with fresh eyes, much of it is astonishingly prescient in its ability to address so many present day issues, especially with regards to technology, surveillance, public space, commerce and social justice. If I didn’t like Haring’s work in the ’80s, I realize now, it may be because I never actually saw it in a sea of depoliticized knock-offs.

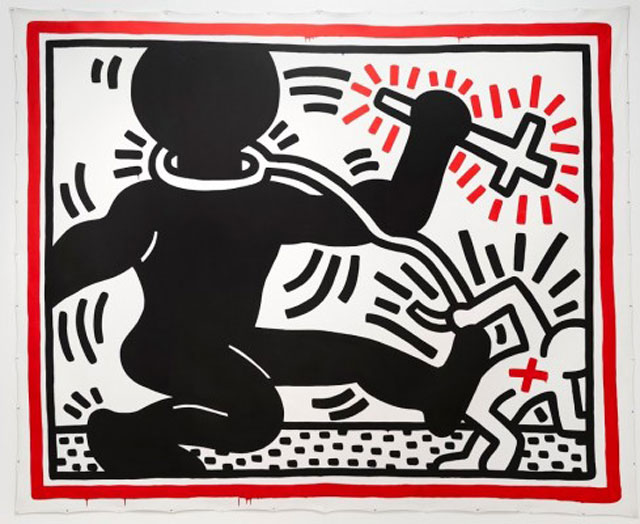

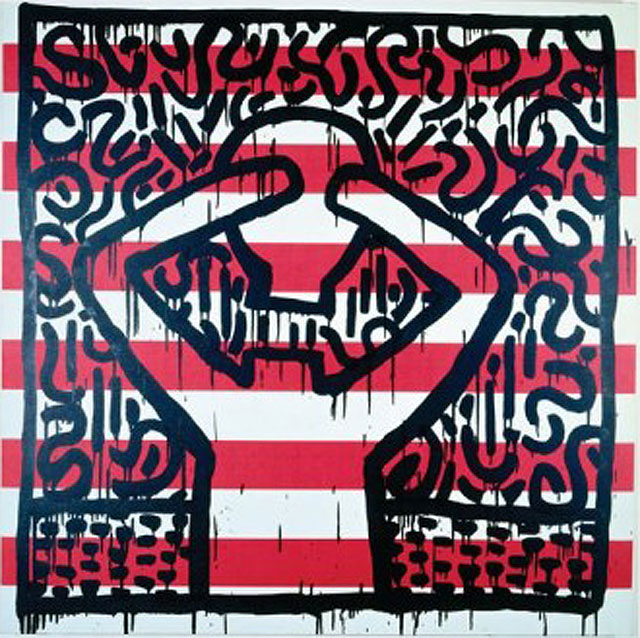

Uncharacteristically, and perhaps amusingly given the venue, the web page for the show at the de Young begins with this disclaimer: “Please note that the exhibition contains certain artworks that are adult in nature; images included on this site may be violent, sexual, and/or political in content.” And indeed, there are a lot of erect penises, if you will, among other explicit stick figure images in this densely packed display of 130 works ranging from graffiti, literally ripped from the walls of New York’s subway, drawing, painting and sculpture. Images of copulation, bestiality and fellatio are everywhere.

Beyond this titillating entre, there is also overt protest and dissent presented as thrilling disruptions and interventions. The earlier work is understandably more rough-hewn and experimental, while the later work is more polished. Throughout, Haring’s irreverence never wavers. In the last room, we see his many layered final paintings; each presents a shift in line quality and a palpable sense of urgency. In an era when an AIDS diagnosis was essentially a death sentence, primarily targeting young men, the artist seemed to spend every last ounce of energy racing the clock.

Whereas the exhibition reminds us how much Haring had to say in his relatively short career, with these final works we are also made aware of how much more he could have said. What, one wonders, would he have made out of the world we live in now, when so much of his work seems to anticipate the future?

A 1983 untitled enamel on incised wood sculpture, created in collaboration with Kermit Oswald, seems to have anticipated our contemporary dependence on technology; the figure with a computer for a brain is rife with salient symbolism. It is inscribed with images of people with telephones for heads and radiating calculators that resemble smart phones; one hand morphs into a barking dog, a symbol of evil, its face a surveillance camera tethered to a prone figure inscribed on its unhinged jaw, ready to consume itself. With this work in particular, Haring’s images are like future-tense hieroglyphics, chronicling much of a world yet to come in a visual language that seemed to anticipate vector line graphics and emoticons.

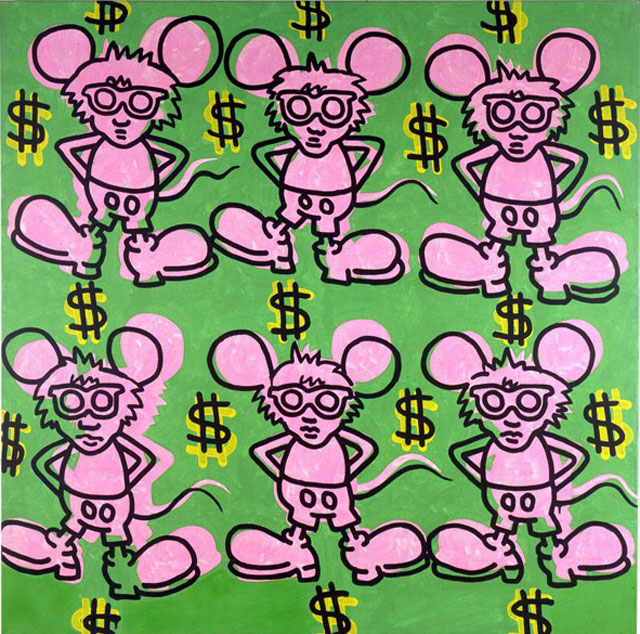

Haring was especially wise to the commercial potential of his work in ways that were also way ahead of his time. Even the scrim outside the museum reflects a copyright mark, suggesting, perhaps, that the museum may have had to license the artist’s work in order to promote it. His Pop Shop in Manhattan, and another later briefly in Tokyo, sold everything from calendars to books to clothing. It closed in 2005, but maintains an active online store today. Its overt commercialism rankled an art world that prefers to see artists oblivious to their own commercial interests, but today Haring seems to have anticipated Etsy and, indeed, Kickstarter.