Racks and shelves of colorful clothing, textiles, tchotchkes, tote bags, tea, cassette tapes and records fill the stalls that occupy Southern Exposure’s spacious gallery. But these are not your typical wares; fists clenched in protest emblazon enough of the goods to start a rhythm and printed blood pours down the sides of throw pillows. Theory of Survival: Fabrications (September 5-October 25), organized by artist Taraneh Hemami, brings together twelve local Iranian artists to grapple with the politics and visual language of dissent. This gallery-turned-bazaar is full of goods to buy and sell, but like any marketplace it is also a site for much cultural exchange.

Each artist was designated their own booth to populate with artistic goods, so the range of work is vast in content and form. In painter Taravat Talepasand’s stall, shirts are folded neatly on shelves and hang for sale. One set of shirts has been printed with an image that riffs off of Raymond Pettibon’s illustration for the 1990 Sonic Youth album Goo. Pettibon’s drawing of Maureen Hindley and David Smith on their way to the Moors murders serial killer trial of 1966 is reimaged by Talepasand as two women in sunglasses and traditional chadors smoking. Across the way, painter Amir Fallah’s booth features chadors and headscarves hanging solemnly against a white wall. Like the name of his booth Failure, these garments appear to do just that. Fallah bleached the heavy fabric with a deliberate fury reminiscent of 1980s acid wash, discoloring the dark cloth with chaotic blotches and streams that seem to whip the pigment from the material. Both artists confront a post-revolution Iran intersecting with American pop culture, illuminating how pop culture itself can be appropriated to become a pastiche language of dissent.

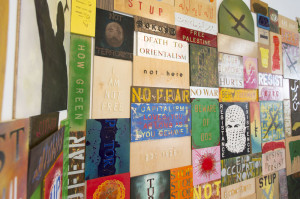

The space as a whole resembles an art fair as much as any bazaar or marketplace. Each “stall” is partitioned by drywall, painted white and built to temporarily and hastily divide. Most of the artists treat their sections like an exhibition space, employing the vernacular of the art world. Art fairs highlight art as a commodity — a connection to mainstream consumerism that is highly debated in the arts. So here, the structure of commonplace bazaar flirts with art fair white cube; there may not be any red dots on the wall, but there are price lists in plastic sheet protectors. You can definitely touch the art, but prices range from $10 to thousands: after all, this is no average store.

Hemami embraces this tension, especially after the troubling experience of seeing her work, and other art that was political in nature, exhibited in Dubai against the backdrop of the hungry consumption of international art fairs and exhibitions. She noticed that as viewers interacted with the art they also allowed themselves to engage with the works’ politics in a way they weren’t necessarily doing within their own lives or cultural spaces. Art added another layer and made it more comfortable to discuss contentious political and social topics. Fabrications attempts to create a space for both the broader public and Iranians to get closer to these politics and histories. Hemami notes, “For many Iranians of my generation, or younger, there is a huge silence around this political time and the revolution. There is a lot of conflict around how people view the political dissent of that time [just after the 1979 Iranian Revolution]. It’s a very uncomfortable subject to talk about.”

So the idea to wrap these ideas in consumer culture was born. Fabrications is a part of a larger project, Theory of Survival, which began while Hemami was doing research in an archive of politically dissident publications from Iran that is housed in the library of the Iranian Students Association of Northern California.