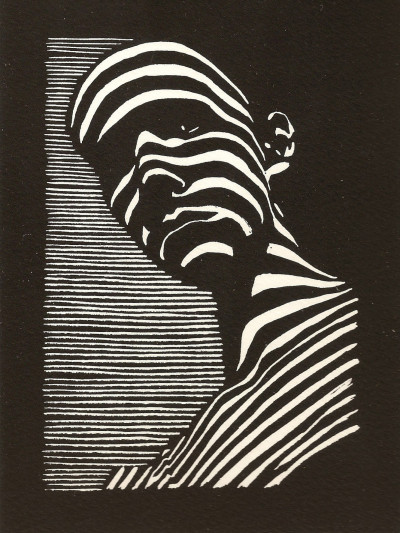

Several years ago, when artist Henry Edward Frank was asked about his availability in a job interview he said he was only busy Friday mornings. “If I can’t have Friday mornings off, I don’t want the job. Those are my block printing hours,” Frank recalls saying.

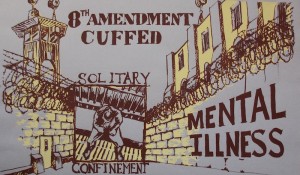

Frank, at the time an inmate at San Quentin State Prison, learned about the the prison’s block printing classes almost immediately after transferring from California State Prison, Corcoran. An inmate Frank knew from Corcoran told him about the classes offered by the William James Association’s (WJA) Prison Arts Project and Frank jumped at the opportunity to take them. At Corcoran, Frank, who has been making art since he was five, spent as much time as he could drawing, acrylic painting, leather making, drum making, and doing calligraphy. It wasn’t until his move to San Quentin, however, that Frank tried his hand at block printing, which he now considers his main artistic medium. One of his prints is now on view, along with the work of twenty-eight other current and former San Quentin inmates, at the Yerba Buena Center for the Art (YBCA) as part of Bay Area Now 7 (BAN7), a triennial of contemporary Bay Area art.

The Prison Arts Project offers art and writing classes at San Quentin several times a day, seven days a week, including linocut, poetry, painting, drawing, mural making, bookbinding, and a partnership with Marin Shakespeare Company. For this year’s iteration of BAN, YBCA’s curatorial team issued a call for proposals for Bay Area arts organizations and the WJA was one of fifty applicants and only fifteen selected participants.

San Quentin, home to nearly 4,000 prisoners and California’s death row for male inmates, may seem like an unlikely artistic hub. But the prison is home to several dozen vocational, educational, and personal programs, such as the associate’s degree–granting Prison University Project, a meditation group, a charitable bike refurbishing group, and a partnership with the Marin Humane Society in which inmates learn to train dogs with health or behaviour issues. Carol Newborg, program manager for the Prison Arts Project, attributes this atypical level of programming to the legacy of Clinton Duffy, San Quentin’s warden from 1940 to 1952. Duffy, a lifelong opponent of capital punishment and proponent of rehabilitation, introduced night school and a series of other programs, even allowing inmates to publish a newspaper and operate a radio station. Duffy was mocked at the time, but there’s no doubt now that programs like the Prison Arts Project have a remarkable impact on prison life.

A recent study of prison arts programs found that a significant majority of participants reported a reduction in disciplinary citations, improved confidence, less stress, and increased happiness. Frank, who beams when he speaks of his block printing and bookbinding classes, confirms this study: “It didn’t really feel like prison when I was in there. It was just an amazing place.”