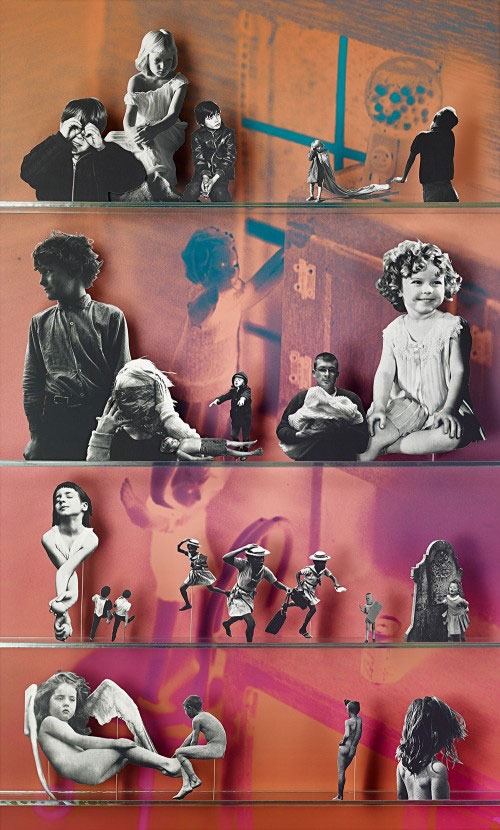

On the ever-eventful corner of Ellis and Leavenworth Streets, in the heart of San Francisco’s Tenderloin, Jessica Silverman’s (relatively) new space is pristine, airy and filled with light, hermetically sealed from the outside world. The current exhibition, a glossy group of large-scale photographs by Matt Lipps, takes full advantage of the space. Lipps’ show, The Populist Camera, is a collection of collections. Sourcing material from personal archives and a series of Time-Life books titled Library of Photography, Lipps arranges crisp black-and-white cut-outs on glass shelves against the polarized backgrounds of his own images. The result is an exhibition of Wunderkammern, cabinets of curiosity that contain samples of thrilling photographic imagery and create a persuasive argument for the continued relevance of analog methods.

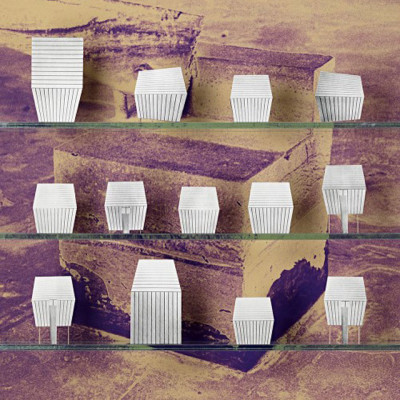

The Library of Photography is a 17-volume book set, published between 1970 and 1972. Those interested in learning about lighting, photojournalism, and tackling the “special problems” of photography could subscribe to the series and study up — one book at a time. The ten pieces in The Populist Camera borrow their titles from different books in the series, providing organizing principles to the more abstract conglomerations of imagery.

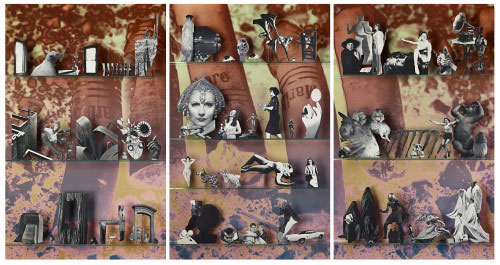

The exhibition opens with an impressive triptych just past the gallery’s front desk. 1973 – 1975 features ten shelves of objects, animals, interesting shapes, and figures against backgrounds of washed out Marlborough cigarette butts. Images of classic beauty rest like decorative plates on the glass shelves, the drop shadows behind them creating enough trompe l’oeil to be momentarily convincing. At second glance, the scale registers: Lipps’ cut outs are presented as is, remaining relative to their size on their respective pages. A giant baby dwarfs an adult cyclist. Three different sizes of reclining women occupy a center shelf.

Lipps doesn’t shy away from including images with abrupt rectangular edges, choosing instead to retain these reminders of the material’s original place on the page. Art provides the most explicit examples of this, in a gradation from light to dark over the course of three levels of abstracted shapes, all against a minty double exposure of a GE electric fan.

The more puzzling the juxtapositions, the more Lipps’ photographs recall the original Wunderkammern. Bizarre and marvelous objects, manmade, natural and inexplicable, coexisted within the same space because the categorical boundaries of natural science, archeology, geology or religious history did not yet exist. Two wondrously weird and unrelated objects in a Wunderkammer could trigger moments of discovery for those with enough imagination to connect the pair.

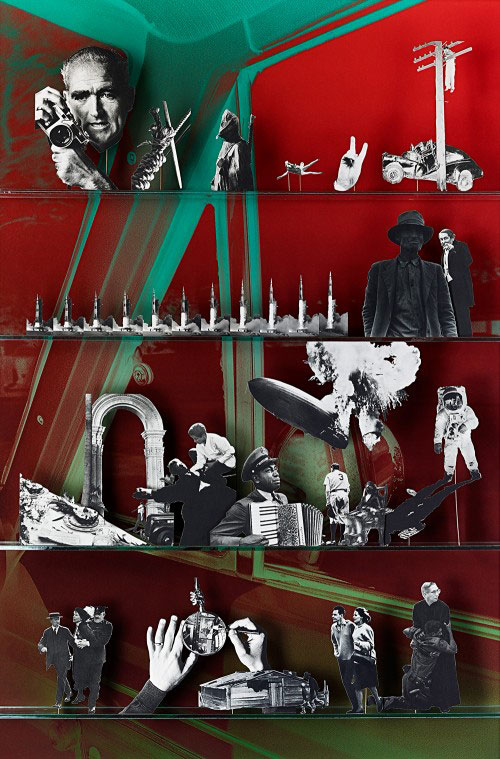

Though each of Lipps’ photographs includes images culled from the same Library of Photography book, the editing process he employs is evident, whether in the selection of background imagery, the cuts of the page, or the positioning on the shelves themselves. In Photojournalism, so many images are easily recognizable that the remaining few beg to be identified. Lipps presents a rebus-like arrangement of significant events — from the Hindenburg disaster to the first moon walk — as a testament to the power of documentary photography. Even the background in this one resembles a Lee Friedlander.