KQED, a San Francisco based public media organization, is interested in broadening participation and attracting and engaging a younger and more diverse audience, especially millennials, for their science media. The KQED science team is one of the largest reporting teams in the West with a focus on science news and it’s YouTube series, Deep Look. Supported by a three-year NSF grant, the team brought together KQED science media professionals, academic science media researchers from Texas Tech and Yale universities, an evaluator from Rockman et al and in the final year the University of Connecticut to study and research science media habits and behaviors of millennials. We called the project Cracking the Code: Influencing Millennial Science Engagement or “CTC” for short.

The study focused on two research questions:

1. How can KQED adapt and expand upon existing research to understand the role of science identity and curiosity in millennial engagement and interest in science media?

2. Which presentations – editorial tactics, platform choices, media elements, and outreach strategies – can increase millennials' curiosity and cognitive engagement with science content, with special attention given to underrepresented and under-engaged audiences within the generation?

These questions were studied using a variety of surveys, questionnaires and interviews that will be reviewed below with links to the complete studies and resources, a recorded webinar and a presentation deck. All of the research studies can be found on the KQED Cracking the Code website.

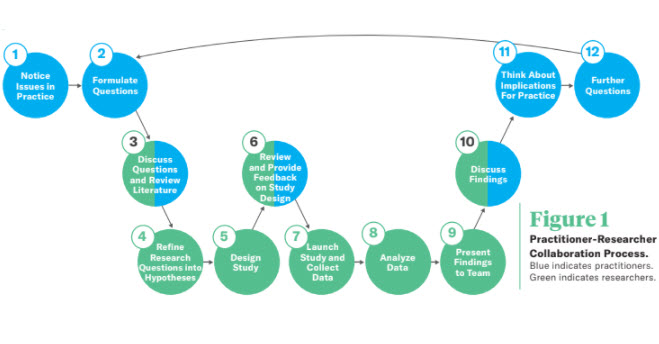

As the team progressed over the course of the investigation, an iterative workflow emerged as portrayed in this diagram below as well as a supportive and unique practitioner – researcher collaboration in audience media research.

Beyond Market Research

Prior to the work on CTC, the KQED science unit relied on market research, data collected from our social media metrics for audience insights. While useful, the data only gave us information on our existing audiences and we want to know more about possible future audiences, individuals that had an interest in science but were not engaging with our content. We came to call this our “missing audience.” We also wanted to understand not only what our audiences prefer – which we gathered through audience reach, top stories, time on page, etc., – but why did they behave the way they did? Through exploratory research, we hoped to get a more complete understanding of our existing audiences as well as our science curious “missing audience.”

The audience research performed in this project was informed by the use of the Science Curiosity Scale” (SCS). The SCS is a research instrument developed by Dan Kahan (Yale University) and Asheley Landrum (Texas Tech University) with their collaborators to better measure science interest through a combination of behavioral and self-reported measures. Science curiosity is defined as one’s motivation to seek out and engage with science for personal enjoyment. The scale is part of a market research/interests type survey that asks about an array of topics (e.g., business, sports, entertainment) to hide the intent to measure interest in science. The scores on the Science Curiosity Scale strongly predict people’s engagement with science media, such as the likelihood that they read a science book in the past year and how closely they follow news about science. Science curiosity is a stronger predictor than ANY demographic characteristic (race, ethnicity, age, etc.). Go here for more on the Science Curiosity Scale.

National surveys on science media habits

To get a baseline understanding of the behavior and habits of science media consumers, we conducted a national survey in 2018 using the Science Curiosity Scale. The focus of the survey was to collect data on how audiences in general engage with science media and specifically millennials and young adults on their cultural and religious beliefs, political affiliations, their interest in science topics and levels of science curiosity.

Some of the key findings included:

- Millennials are more science curious than other generations

- That science curiosity can overcome political and cultural beliefs

- That millennials preferred video and social media for consuming science media engagement

- Gender differences in science disciplines like computer science and technology, among many other things.

- We were also able to identify our missing audiences through the survey: millennials of color and white college educated women with children.

To wrap up our project, we conducted another large survey in 2021 need link. The survey was designed by the KQED and Texas Tech research team and was fielded by YouGov in August 2021. We asked many of the same questions as the original survey, but we also surveyed more audiences (in addition to the nationally representative sample) and dug in deeper to questions that were generated as a result of the past three years of research.

Some top level takeaways from that survey include:

- Curious Audience: Science curiosity is the strongest predictor of engagement with science — way above any demographic characteristic. However, science curiosity can vary by demographics.

- Topics of Interest: Adults (40 and younger) are most interested in nature, wildlife, and psychology/behavioral science. Our youngest participants are the ones most interested in climate change. Health and medicine become more important with age.

- Platforms Used: Search engines and websites are most commonly used to find science content (public media). YouTube is also popular. TikTok is most commonly used by Gen Zers and is the least popular platform for science among millennials.

- Missing Audience: Black and Hispanic millennial women seem to be the most frequently “missing” audience for science from platforms such as TikTok, podcasts, live radio, and YouTube. This is not the case for Gen Zers.

- Science Stories: Stories that explain something audiences are curious about in nature and the environment are much more popular than any other type of story, including news about scientific discoveries and climate change.

- Story Credibility: Curious Gen Zers trust their gut intuition about whether stories are credible. Millennials and open Gen Zers prioritize peer review and expertise.

Deep Look — YouTube and Gender Disparity

For those of you not familiar with our video series, Deep Look, it is a digital video series that explores big science concepts by going very, very small, to see nature up close ... sometimes uncomfortably close, but all in good fun. And the series is by nearly any measure a great success. On YouTube, where the show is distributed, we have almost 1.8 million subscribers and have garnered 325 million views and 2/3 of that audience is aged 18-34, a young, mostly millennial audience that KQED and the PBS system as a whole is eager to serve.

But Deep Look has a problem. For almost every one of our 135+ episodes, the percentage of women who watch is considerably lower than the percentage of men, a disparity also seen by many of our creator colleagues on other science shows on YouTube. On average, about 70% of Deep Look’s YouTube audience is male and only 30% is female. It’s true, there are slightly fewer women on YouTube in general, at around 40%, but still this disparity is distressing to our team.

So, why aren’t more women watching? One hypothesis was that the YouTube algorithm — that recommendation engine that predicts what videos you might like and serves them to you in real time — is suggesting our videos more often to men than women, for its own business reasons that don’t necessarily line up with our editorial goals.

Another hypothesis was that the subject matter may be aversive overall to women more than men since Deep Look is a show about insects, arachnids, undersea creatures, amphibians and the like.

So we conducted an initial study in collaboration with Dan Kahan (Yale University) to see if we could replicate this gender disparity off the YouTube platform to confirm if the disparity was platform driven or if it was the content that women found uninteresting (or off-putting) and why.

The study, “Cracking the Code: Survey Takes A 'Deep Look' at Science Video Audience and Gender Disparity,” produced the following key findings:

- The YouTube algorithm is not likely determining our gender imbalance of 70% male vs. 30% female

- When women and men of high-science curiosity watched the content, engagement was equal

- People’s level of “disgust sensitivity” did not predict the likelihood of agreeing to watch a Deep Look video.

- Given that getting disgust sensitivity doesn't appear to be a factor, and that both men and women seem to enjoy the video the same if they get to the point of watching it — this led us to question whether there is something happening —- an inhibition of some sort — that influences the respondents decision to watch.

Deep Look - Factors of Inhibition

To follow up on this initial study, we began to consider why women may feel more inhibited, or reticent, to watch a Deep Look video than men? Some prior literature from psychology and communication suggested that women may perceive science as not being “for them.” So, how could we indicate that content is for women using the factors commonly believed to have a significant influence over people’s decision to click on a video in the real world, such as thumbnails, titles and descriptions? Could changes to one or more of these factors mitigate — or exacerbate — this apparent inhibition to choose to watch? The Deep Look and research teams followed up with several more studies to try to answer these questions.

In our study, Cracking the Code: What’s Keeping Women from Watching Deep Look’s Science Videos? No Easy Answers, we worked with Dan Kahan to conduct a survey which included an image of a woman in the YouTube thumbnails of our Deep Look episodes. The goal was to show women that the content is for them by showing an image of a woman enjoying the content. We wanted to study if this tactic would encourage more women to click on the link to watch Deep Look videos. The survey also studied possible disgust sensitivity (someone being disgusted by the title, image or content in the videos) to find out if that was a factor in why women decide not to click on Deep Look content. The findings from this study were inconclusive.

In our title studies, Do Stories about Health – and Sex – Draw Women to Watch KQED’s Deep Look Science Videos?, the KQED team worked with the Texas Tech researchers to continue to explore disgust as a possible inhibiting factor to watching Deep Look as well as other factors that could influence watching the video due to their titles. For example, the Deep Look producers had noticed that more women watched episodes with a health and sex/mating theme. This was supported by an analysis of title themes: episodes with a sex/mating theme emphasized in the title had a greater proportion of female viewers on average compared with episodes that didn’t have this theme emphasized. The same seemed to be true for titles that had a health or medicine angle.

This led the team to question: Could changing a title to emphasize sex/mating or health/medicine lead to a greater number of female viewers? To examine this, we conducted a few survey experiments for which we manipulated whether participants were asked if they would watch a video after seeing the original title or one with the sex/mating or health/medicine emphasis. The results were somewhat inconclusive: although a greater percentage of women agreed to watch the Deep Look video when it had the health/medicine title than the original title, the results were not statistically significant. Furthermore, we did not find a difference between desire to watch the episodes when shown the sex/mating title versus the original one.

We also conducted a series of Facebook experiments using their advertising tool as a complement to the survey experiments for the Deep Look title testing. The advertising platform provided us with the tools we need to conduct more in-depth audience research. Similar to other digital advertising tools such as Google, Twitter, YouTube, and others, Facebook allows users to reach an intended audience based on interest, age, gender and location.

For our How Women Engage with Deep Look: A Facebook Science Content Experiment the science engagement team worked with the Texas Tech researchers to design a test to see whether different titles drove more or less traffic to an episode. Our science engagement team works with reporters and video producers to attract audiences to our science content and engage them through the creation of additional content such as behind-the-scenes videos and photos, polls, contests, live events and social media advertising. The test was designed to engage different intended audiences, specifically among audiences that are female and likely science curious. The results in this particular Facebook experiment, across all audiences, showed that a health-related themed title was preferred, and a more significant proportion of women clicked on them.

The science engagement team was also curious how our behind-the scenes content could influence more female engagement with Deep Look. For Cracking the Code: What’s the Value of Behind-The-Scenes Content for a Science Series like KQED’s Deep Look?, the KQED team worked with Texas Tech researchers to compare engagement with a Deep Look episode that included behind-the-scenes photos, produced behind-the-scenes full episodes, unedited short outtakes, and images of a host on screen introducing the Deep Look episode. The engagement team felt that the produced behind-the-scenes episodes helped increase engagement, but the cost of producing such content is very high. This research suggested that the much less resource intensive behind-the-scenes photos are as engaging as expensive produced episodes. Furthermore, even less curious audiences reported higher engagement with the videos when behind-the-scenes photos were present.

Since these research results came out the Deep Look team has implemented a robust behind-the-scenes social media engagement strategy with consistent posting of behind-the-scenes photos and videos of producers out in the field, including background posts letting fans know when a story has been cleared for production and livestream events that talk about and show how Deep Look is able to capture such amazing footage of tiny animals and plants in their natural environments. The content would be shared on social media and on the Deep Look episodes.

Finally, the Deep Look team conducted a study with University of Connecticut researchers (in collaboration with the Texas Tech team) that focused on how women’s science identity may contribute to their engagement. The research, titled Study Advances Understanding of Women’s Intentions to Watch Deep Look YouTube Videos, was designed to better understand gender differences in science engagement in order to attract the “missing audience” of women viewers to Deep Look YouTube videos.

The focus on gender differences in science engagement is important for helping KQED Deep Look (and other educational media outlets) identify ways to expand viewership, and this focus also is important for helping science communication researchers better understand how gender and identity influence engagement with science content. Key findings of this study was that women tended to prefer videos with visually attractive images, and preference for the “creepier” insect-type videos increased with increasing science identity. These studies provided us with takeaways about both how to increase our female audience and how to facilitate researcher-practitioner collaborations.

The collective findings over all of the Deep Look studies include:

- Titles that emphasize relevant and useful information (health, medicine) appear to be more attractive to women than titles that do not emphasize such content. This leads us to a future research question: Do women have more instrumental goals for consuming science video than men? Since having conducted this research, Deep Look has more heavily considered emphasizing such titles (when appropriate) to help attract more women viewers.

- Though thumbnail selection has always been considered important, these studies have made the Deep Look team focus even more on thumbnails’ aesthetics and attractiveness to draw women in, specifically intense colors, images that elicit curiosity, or are perceived as "charming."

- Deep Look plans to expand our behind-the-scenes content since it engages our missing audience of women, both science curious and not. For example, now many behind-the-scenes photos are collected by producers on site and are posted by the engagement team on KQED social media.

- Though conducting large survey experiments may not be practical for audience engagement teams, we have a better understanding of how to experiment with social media testing to reach missing audiences.

Science News

Besides our science digital video team, the science unit also included an award-winning journalism team of editors, reporters and information designers. They reported on all types of science news with a focus on climate change, health, environment, wildfires, earthquakes and water. They cover daily news – short pieces and interviews – as well as features and multipart series for radio broadcast and the KQED website.

News Headline Study

At the beginning of our NSF grant as a proof of concept of how the news team would work with science communications researchers, we conducted a brief science news headline study in collaboration with Texas Tech researchers. Although the study, Experimenting with Science News Headline Format to Maximize Engagement, did find differences in how individuals might evaluate the credibility of a headline and of a story based on the headline format, whether individuals wanted to read a story or engage with a story did not seem to differ based on headline format.

Key findings from this survey were:

- Stories with forward referencing headlines (Ex. Here’s What Little Earthquakes Tell Scientists About the Likelihood of the Big One ) had a greater probability of being categorized as “real” news than the traditional or question (Do Little Earthquakes Mean the Big One is Close at Hand?) headline formats.

- Although science curiosity predicted anticipated engagement, participants generally (and millennials in particular) saw question-based headlines as less credible.

- Moreover, they were less likely to categorize these stories as real news (choosing “fake news” or “satire”) than they were the other headline types.

- Takeaway — The intuitive method of sparking curiosity via asking questions to increase engagement could be seen as click bait (internet content whose main purpose is to attract attention and encourage visitors to click on a link to a particular webpage) and result, instead, in loss of credibility — something that the news media, and science news in particular, cannot afford to lose.

News Awe Study

The primary interest of the news team was to find out if a different news writing style would drive deeper engagement with our science news articles. Through existing studies we learned that people can feel experiences like connectedness and vastness, in reading the written word. We wanted to look at how our story framing and construction, and the narrative tools we bring to writing can foster these experiences and enhance engagement with our audiences. We wanted to be able to do this reporting on the largest and most relevant issues facing our audiences – issues like climate change and environmental justice. Our interest was to cultivate new, young audiences by offering them more than useful knowledge – by offering them experiences that connect them to their larger world, in what you might call a “driveway moment,” those times you stop doing whatever you are doing and get caught up in the story you are reading online.

To conduct this study, we needed to create a survey instrument –- an “awe experience scale” that could capture differences in “awe” from reading news stories. Vastness and connectedness are the dimensions of awe most strongly associated with participants’ explicit ratings of awe. If we can periodically work awe into our news writing we hope to engage our existing audience more deeply and possibly attract new audiences.

Further work on the awe study was permanently put aside by March 2020 as COVID-19 began to grow into a pandemic. As well, due to social distancing, mask requirement and lack of the ability to travel, the team was unable to execute further study, which would have required trips to Texas Tech University and the recruitment of individuals for tests at Texas Tech’s Psychophysiology Lab. The lab houses state-of-the-art technology for studying all facets of audience response to media messages — video, audio, online, commercial, informational and more.

RAPID and Disaster Studies

In addition to CTC, KQED and Texas Tech University also received an NSF RAPID grant to understand the COVID-19 information needs of its community to assist KQED science journalists with their health coverage. The project, Influencing Young Adults’ Science Engagement and Learning with COVID-19 Media, conducted studies to identify COVID-19 and health knowledge gaps, understand COVID-19 misinformation narratives on social media, know how best to communicate health and science information to the public, and conduct an in-depth process evaluation to capture best practices for crisis reporting.

Coverage of COVID-19 required an increased focus on what we came to call “disaster” or “crisis” reporting and the opportunity to study the needs, rhythms and flow of this type of situational reporting became a priority. The team designed a real-time COVID-19 news blog with timely updates and news you could use posted on the KQED website and social media. Coverage for both the blog, engagement and daily and feature news required long hours and new processes for the team.

With the support of a NSF RAPID grant, the team pivoted to focus on understanding the workflow of covering a disaster and engaging our audiences in information that is critical for getting through the pandemic.

The team conducted a series of research projects to assist the editors and reporters. Researchers conducted studies in understanding the types of misinformation that was appearing on Twitter, knowledge gaps across the general public and younger adults about the virus and treatment, use of visual information to explain critical health information about COVID-19 in news articles and on social media, and a process evaluation to document the new science “disaster and crisis” news reporting reality that was emerging due to the rapid need for information. The science managing editor used to say “Science didn’t break, it oozed.” That was no longer the reality.

All of the studies conducted through the RAPID grant can be found on the Cracking the Code website. A summary of the project, RAPID: Filling Knowledge Gaps and Crisis Reporting gives an overview of the project and the individual studies.

Process Evaluation

The focus of the evaluation conducted by Rockman et al was to assess the impact of a practitioner-research collaboration on audience engagement, research processes and applied practices as a result of the research. KQED and Texas Tech University had the rare opportunity to truly model an in-depth collaboration and gain professional knowledge for future application and learning. It is not often that science communication researchers have the opportunity to embed with media professionals and conduct applied research in real world situations. And vice versa.

Our evaluator gathered data and observed the teams between October 2018 - August 2021. He conducted interviews with KQED science unit (Deep Look, News), the science engagement staff, administrative staff, Texas Tech University and the University of Connecticut researchers and consultants and project consultants. He recorded in-person/virtual observations of project meetings that took place weekly.

Both KQED and Texas Tech came away from the project’s final year with a greater understanding and appreciation for the complexity and nuance of conducting audience research. Each recognized the advantages and limitations of applying different research strategies, both quantitative and qualitative. Members of the research team placed more value on the media practitioner’s professional experience and knowledge as a tool to conduct research, while KQED science staff discerned that science communication research was as much a “process” as producing a science series or developing an investigative story feature.

The RAPID Process Evaluation Report provides several takeaways for the future including:

Lessons from Team Building

- Respect and appreciation of skills, knowledge and working methods across teams

- Greater appreciation of the importance of audience research

- Applications for applied and basic research for the study of audience engagement and solutions

- Adaptation, consensus building and multitasking

- A process to validate professional knowledge and abilities

- Career-building and professional development opportunities for project participants

- Wider application of social media tools and research beyond market research

- Methods for engaging tensions to foster collaboration

- Processes that can be replicated by other media organizations and academic institutions

- Collaboration among multiple academic institutions

The team also experienced difficulties that were problematic to overcome:

- Real-time conclusions from research studies

- Little time for collective reflection

- Overlapping work and project demands

- Lack of adequate formative planning

- Insufficient organizational-wide communication

- Report writing and findings dissemination gaps

Conclusion

Both KQED and Texas Tech University came away from the Cracking the Code (CTC) collaboration with a greater understanding and appreciation for the complexity and nuance of conducting audience research. Each team recognized the advantages and limitations of applying different research strategies, both quantitative and qualitative. Members of the research team placed more value on the media practitioner’s professional experience and knowledge as a tool to conduct research, while KQED science staff discerned that science communication research was as much a “process” as producing a science series or developing an investigative story feature.

Even through a global pandemic, wildfires, corporate reorganizations, layoffs, and a shift to online academic classes and restrictions in conducting face-to-face research in the academic space, the collaborative framework and trust between the partners strengthened, and research activities continued, almost unabated. The collaboration was flexible (and risk averse) enough to incorporate the participation of additional research consultants, and the inclusion of new and innovative methods of data collection tools and methods to deepen the work. In addition, while working on CTC, the same collaborative team also conducted parallel research activities associated with an NSF-funded RAPID/AISL grant exploring science communication methods influencing millennials and young adults’ science engagement focused on COVID-19 media.

The success of the CTC collaboration offers the potential for further types of these research opportunities. Science media practitioners and science communication researchers need to find ways to address long-standing cognitive and process differences, and overcome thinly informed assumptions to jointly conduct activities that benefit the field and the public at large. CTC has demonstrated the power of creative tension to stimulate innovative thinking and problem solving.

Cracking the Code Project Summary Presentation Deck and Webinar link, August 25, 2021