One of the more remarkable migrations among marine animals occurs each year right outside the Golden Gate.

One of the more remarkable migrations among marine animals occurs each year right outside the Golden Gate.

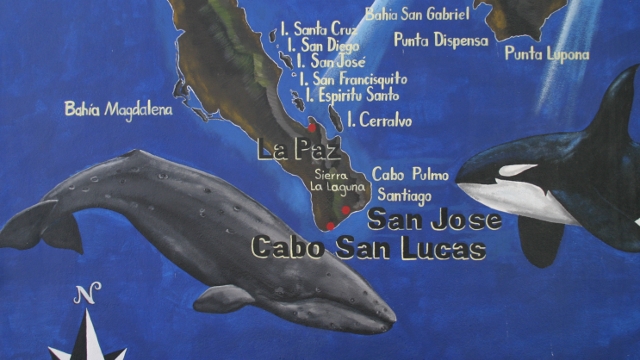

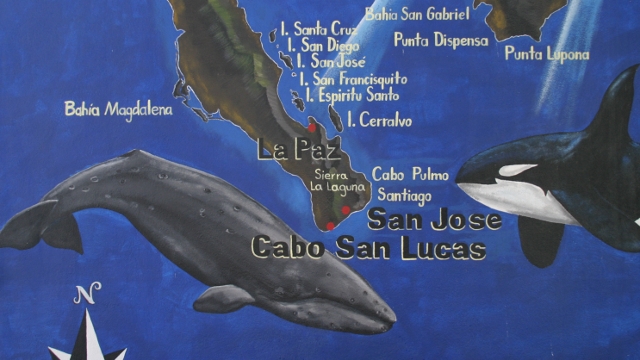

In late fall, the California gray whales passes south along our shoreline to the warm waters of the Sea of Cortez and the lagoons of Baja California, Mexico. Leaving the rich feeding grounds of the Bering and Chukchi seas off Alaska, these baleen whales travel along the coastal margins traveling a distance of approximately 6000 miles to breed and give birth. This round trip of 10,000 to 14,000 miles is considered among the longest annual migration of any mammal. Frequently these whales can be seen from our shoreline with great viewing site off the Point Reyes National Seashore or off Point Montara to the south. The whale is considered a conservation success story because protections instituted in the early 1930's have allowed populations to rebound from possibly less than 1000 individuals.

Leading my last wildlife trip of the year with SF Bay Whale watching last weekend, we spotted a resident gray whale at the southeast Farallon Island, likely an individual among the two hundred or so considered to be resident. These whales are generally juveniles who do not participate in the migration but feed along the shores of California. As opportunistic feeders, the whales scrape along the bottom filtering out crustaceans with their baleen, or scoops krill from the water or even in kelp beds.

As an undergraduate I studied these whales in Laguna Ojo de Liebre (also known as Scammon’s Lagoon after the infamous whaler of the name) and Guerrero Negro in the Baja Peninsula. Camping along the margins of an estuary, we counted and identified whales, monitored movements and even dived the lagoon to observe behavior and collect bottom samples. At that time it was believed that the whales did not feed during their visit to Baja, or along the way, but relied instead on the fat stored from the rich feeding grounds to the north.

Our observations of feeding whales, the verification of food in the lagoons, and other observations of feeding along the coast helped disprove that theory. Gray whales are opportunists, and this opportunism of feeding, migrations and non-migration may have helped the survival of the species. Back in the day before tighter restrictions were in place in Mexico, we commonly paddled our longboards across the lagoon to the sand dunes separating the calm waters from the sea. Juvenile whales would bump our boards and adults 40 feet long passed a hand's breadth beneath us -- with a grapefruit-sized eye staring back at us. Friendly whales frequently rubbed their parasites alongside our inflatable dinghy, as whales spy-hopped, breached and spouted all around us as we collected our data.