Image CreditShould the Electoral College be reformed?

Image CreditShould the Electoral College be reformed?

Step 2 of 5

- Yes? But have you considered...

- No? But have you considered...

… that the Electoral College holds to the framers’ original intention that we live in a constitutional republic, as opposed to a direct democracy?

No doubt, our government’s legitimacy is founded on the consent of the governed, but even a cursory glance at the Constitution leaves little doubt that we live in a constitutional republic, not a true democracy. Though our system of government is similar to a democracy in that it uses a democratic system to elect many of our governmental representatives, that government’s power is both created and limited by its vivifying document, the Constitution. At nearly every turn, the Constitution restricts unchecked power in government — including, in the case of the Electoral College, the will of the people.

Similarly, the framers intended that political power be divided between the states and the federal government. That means that come election time, each state, acting as a unified political entity via the Electoral College, is empowered to register its choice in the presidential election. It’s an integral component of our republic, and if we were to scrap the Electoral College in favor of a nationwide popular vote, it would fundamentally challenge the federal system prescribed in the Constitution.

After all, if we were to elect our president by direct popular vote, proponents of the Electoral College argue, what is to stop us from overhauling the Senate? Like the Electoral College, the Senate, which gives each state two representatives regardless of the state’s population, flies in the face of the democratic principles of proportional representation and one person, one vote.

But why stop there?

The House of Representatives is designed to represent each state according to the size of its population. But if we are really committed to proportional representation, shouldn’t we redraw a state’s congressional districts for each election? After all, it is only by tinkering with these minor discrepancies that we can ensure that each district is equal in population — and that each vote is equal.

In so doing, however, we will have so forcibly restructured our system of government as to make it unrecognizable.

… that the Electoral College doesn’t accurately represent the will of the people?

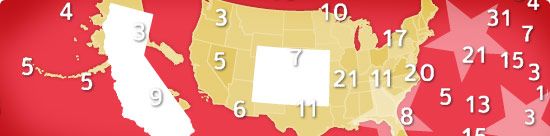

In an effort to guard against regional factionalism, the framers devised the Electoral College to give more weight to voters in sparsely populated rural areas than to voters in more densely populated regions. They did this by allotting each state a number of electors that is equal to the number of politicians in that state’s congressional delegation. The effect is that states like Wyoming, which according to 2006 Census figures has a population of just over 500,000 people, has three electors: One for the state’s sole member of the U.S. House of Representatives and two for its pair of Senators. Meanwhile, California, which had a population of roughly 36.5 million people in 2006, has 55 electors.

The net effect is that an electoral vote in Wyoming (which has roughly 233,000 registered voters) comprises roughly 78,000 individual votes, but an electoral vote in California (which has approximately 16 million registered voters) is composed of about 291,000 votes. Put simply, a ballot cast in Wyoming is about 3.75 times more influential than a ballot cast in the Golden State – and that’s just not fair.

Regardless of the system’s rationale, opponents of the Electoral College argue that by giving small states more electoral power, relatively, than their larger neighbors, the College in effect undermines the notion of one person, one vote. Moreover, they argue, since the College favors voters in smaller states, it inaccurately gauges the popular will of the entire country, unfairly diminishing the proportional sway of urban centers and artificially increasing the power of rural voters.

Opponents add that the Electoral College’s winner-take-all system is a blunt instrument that misrepresents popular attitudes. Not only does it potentially silence 49 percent of a state’s voters, they argue, but it also makes it extremely difficult for a legitimate independent or third party candidate to gain a foothold on a national level. By way of example, third party presidential candidate Ross Perot won 19 percent of the popular vote in 1992, but because his support was dispersed throughout the country, he did not receive a single electoral vote. But even if such a third party candidate managed to win a plurality in a few states, the Electoral College would not register the candidate’s support in other states, which, like Perot’s, could be well into the double digits.

By ignoring a potentially sizable constituency, opponents argue, the Electoral College extinguishes the possibility of third party candidates, strong-arms voters into an artificial choice between Democrats and Republicans, and fails to accurately reflect the will of the people.

Step 2 of 5