When Justin Lane and his family prepared for the recent PG&E power shutoffs at their home in Sonoma County, they counted on using their cellphones to get emergency notifications and updates about the nearby Kincade Fire that had erupted in their area days earlier.

Here's Why You Lost Cell Service During PG&E Power Shutoffs

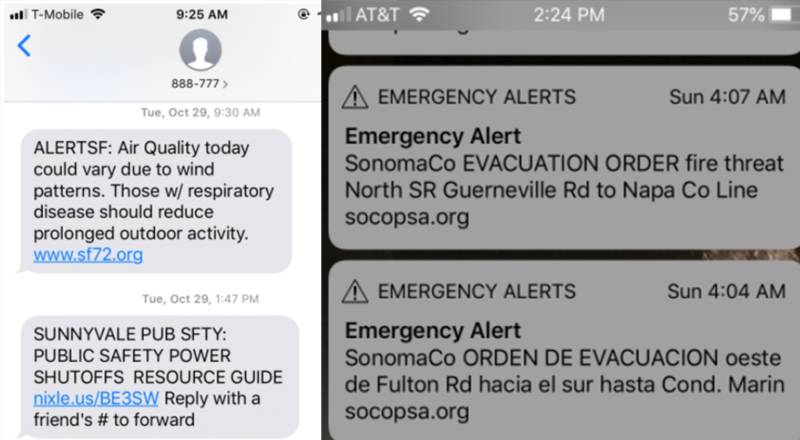

But then, Lane, his wife and their two little girls found themselves in the dark on Saturday, Oct. 26 — power and communications, too. They’d relied on the emergency Nixle and SoCo alerts during the 2017 North Bay fires that devastated communities near their own, but now had no idea if they needed to evacuate or what was happening with the shutoff.

“This time, they were basically unusable,” Lane, 40, a home inspector from Cotati, said of the alerts — some that came in sporadically, though they couldn’t open links to read them. “You can't rely on that when you don't have internet … . It's really not a reliable means of keeping people informed anymore as much as we thought it was.”

What Lane and his family experienced was a problem that officials have been worrying about for years: the lack of backup power for cell towers — and no federal or state requirement that telecom companies provide it. In the wake of the power cuts, 23 members of the state’s congressional delegation have called for a hearing into the broader communications failures, and the California Public Utilities Commission said it’s investigating.

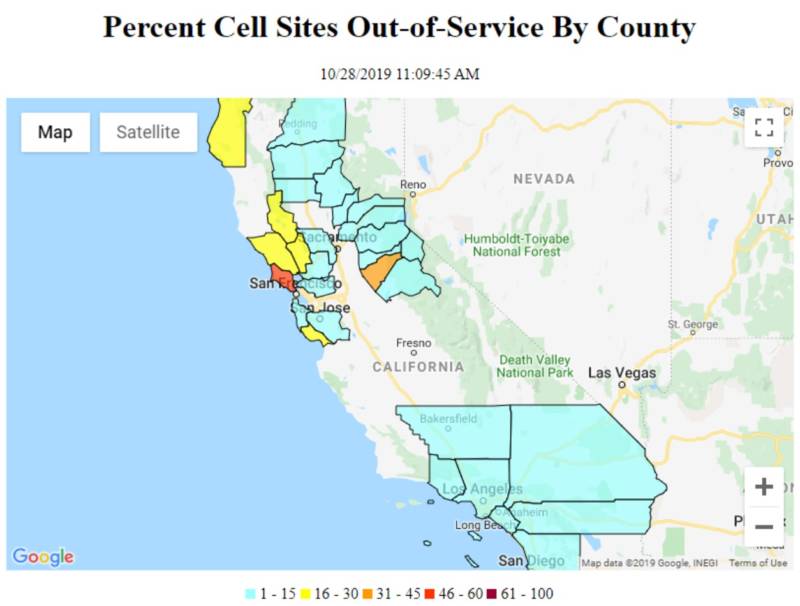

Cell Coverage Problems Peak Locally

In the Bay Area, the cell problems peaked on Monday Oct. 28, with 57% of towers out in Marin County, 27% in Sonoma and 19% in Napa County — mostly due to power issues, according to voluntary information submitted by telecom providers to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

That happened as PG&E prepared for widespread back-to-back shutoffs — meaning that some of its customers who were already in the dark, like Lane, wouldn’t get power restored until after the second outage (his family got it back after five days).

The cell problems continued throughout the week. What this translated into for some people on the ground in places like Marin, Sonoma and Alameda counties: No coverage — unless they traveled to find power, no emergency notifications (including from schools about closures), or sporadic text messages coming through, though it was unclear if they were timely or dated.

Statewide, about 3% of towers went out during the height of the power cuts last Monday as fires raged in Northern and Southern California. FCC said the number of cell site outages didn’t necessarily correspond to the availability of wire service since providers can lean on other tools, like roaming agreements and mobile towers on wheels, to provide coverage.

California’s congressional representatives and the CPUC said the problems were nothing new, citing failures during the historic 2017 storms and the North Bay Fires later that year, plus last year’s Camp Fire.

The FCC doesn’t require wireless providers to have emergency backup power sources, nor does the CPUC, said Ana Maria Johnson, program manager at the Public Advocates Office, an independent group within the commission.

The duration of the several PG&E power shutoffs in October — some lasting many days — highlighted “how unprepared the utilities (telecom companies) are to ensure continuous services during these long durations of no power,” she said.

State Sen. McGuire, whose district covers the North Coast from Marin County to the Oregon border, introduced a bill earlier this year to require a minimum of 48 hours of backup power at cellphone towers in high-fire-threat areas. The Legislature will take that bill up again in January.

McGuire said telecom executives in June assured him that what happened with the cell towers last week wouldn’t happen.

“Cellphones aren't just about checking the latest Facebook status. It's about life or death. Cellphones are our lifeline during these power outages and during emergencies,” McGuire said last week. “For too many years, the state and federal governments have relied on the industry to do the right thing voluntarily. And it's become crystal clear that simply asking them to voluntarily commit to backup power doesn't work.”

CPUC spokesman Christopher Chow said the commission was investigating the problems and developing requirements for providers, but that the communications industry is arguing that the CPUC does not have the authority to regulate them.

FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel tweeted that the federal agency also needed to investigate the cell tower failures in California.

“When it does it needs to reckon with how rolling back regulations and not requiring backup power have made it harder to reach out in disaster,” she said Friday.

The FCC didn’t respond to a KQED request for comment about whether it was considering requiring such a backup in the future.

Telecoms Scramble for Backup Power

Telecom providers told KQED they deployed backup power sources like fixed and permanent generators that ran off fuel, plus batteries, in some areas during the shutoffs.

AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, U.S. Cellular and Verizon said they maintained service for most of their customers.

T-Mobile said some of its customers in Sonoma, Contra Costa, Alameda and Marin counties may have had issues with its service. Sprint said a number of sites may have experienced disruptions, but that “our teams refueled generators that were in use as quickly as possible.”

U.S. Cellular, which had nine cell towers impacted at the peak of the shutoff, said its customers in Humboldt, Lake, Mendocino and Plumas counties were most impacted.

“The utility shutdown was so unexpectedly widespread that most of our network had to rely on backup power at some point in time and we did not have enough power sources to cover all of our cell sites,” the company said Tuesday in a statement. “Had the power outages gone on for much longer, getting access to fuel to keep our generators running would have been a significant issue we believe.”

AT&T said it dispatched hundreds of additional generators and technicians from across the country before the power cuts and did have some equipment get damaged in the Kincade Fire. During the shutoffs, T-Mobile said it deployed (and refueled) generators to more than 260 sites, and Verizon said it had generators and backup batteries at the majority of its cell towers — though "discrete areas" of its network would "experience service disruption or degradation" due to topographical and other technological constraints.

Though most cell towers have some type of backup, McGuire said, “Here's what we know: It's not sufficient.”

For cell customers, the telecom providers plans' and backups don’t provide much comfort.

Lane, a Verizon customer, said that, moving forward, he was going to “brace for the worst.”

“I don't see how they can fix it,” he added. “The cellphone companies rely on the same power for the most part that we do. And if they're out for an extended amount of time, then I'm expecting this to happen again.”

KQED News' Peter Jon Shuler contributed to this report.

Did you have trouble with your cellphone service? Share your story with the reporter: mleitsinger@kqed.org