It’s one of the most confounding sights of California’s recent firestorms: One home is completely destroyed, and another right next door is still standing, even untouched.

Who’s Checking Your Neighborhood for Flammable Brush? Maybe No One

Might be luck. Or it could be because that homeowner took care of the property’s “defensible space,” an area around the building where flammable brush and grass have been cut back, depriving the fire of fuel.

Experts say even a few homes surrounded by too much growth can put an entire neighborhood at risk. So in many parts of the state, inspectors go door to door, checking a home’s defensible space and issuing citations for violations.

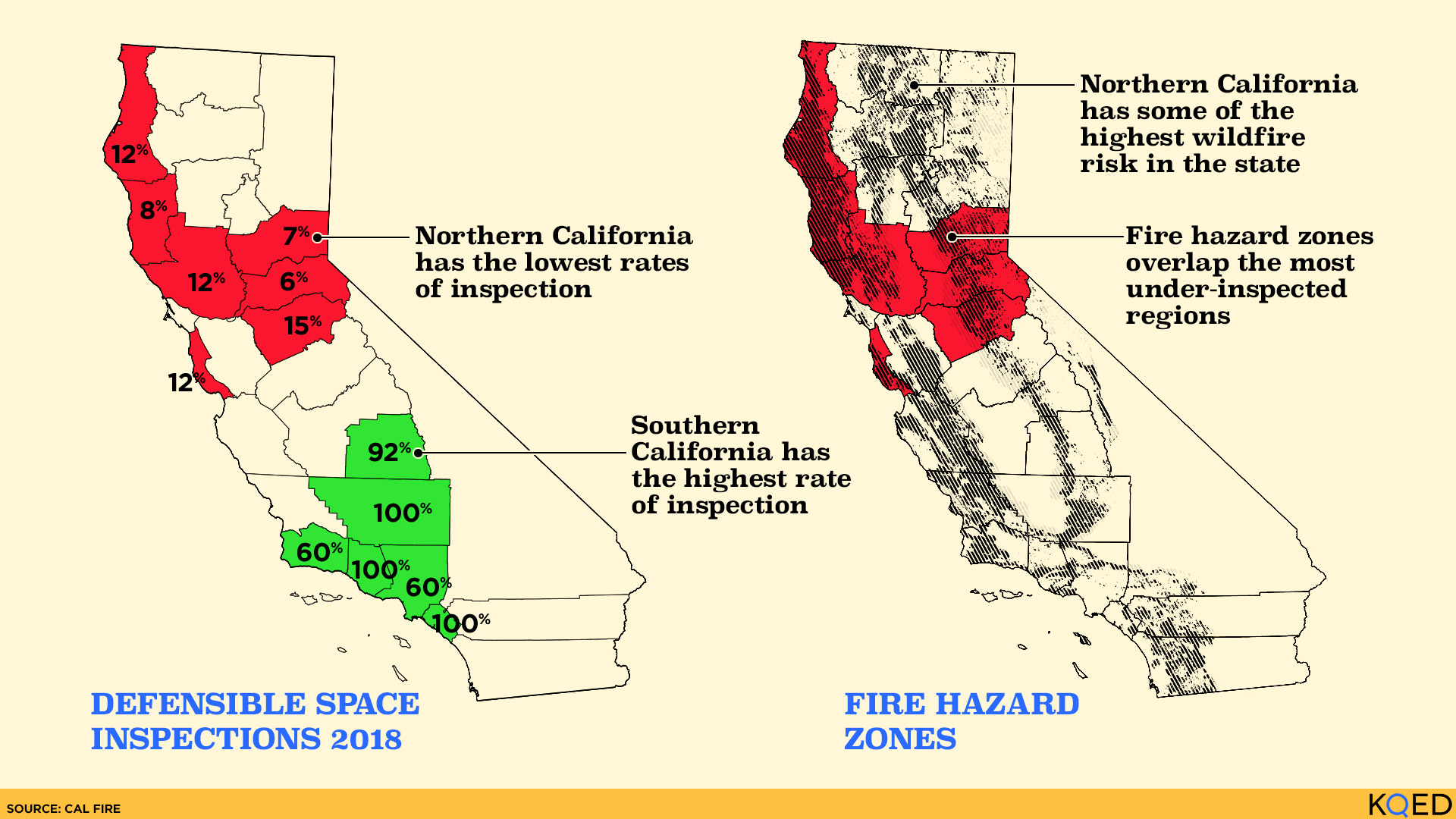

But a KQED investigation has found homes and buildings in Northern California, in some of the most at-risk fire areas in the state, are rarely inspected by Cal Fire, the state firefighting agency responsible for checking defensible space in much of California.

In one Cal Fire region in the Sierra Nevada, just 6% of properties were inspected in 2018. In the Bay Area, Cal Fire inspected just 12% of properties in its jurisdiction that includes Napa and Sonoma counties.

Meanwhile, in Southern California coastal counties, county fire departments are checking homes at much higher rates, with some counties looking at 100% of properties and sending homeowners multiple reminders to make their houses safer.

“We should be doing more, doing better,” said Max Moritz, a wildfire specialist with the University of California Cooperative Extension, after reviewing the findings. “We need to have more people aware they live on a fire-prone landscape and taking action.”

Cal Fire, for its part, says it’s struggling to meet its inspection goals due to a lack of inspectors and resources.

For many Californians, a defensible space inspection will be the only exposure to wildfire planning they get.

“There’s not too many other ways people will learn about the vulnerability of their own home other than having an inspector or firefighter at their property,” Moritz said.

Lake County: Many Fires, Few Inspections

One place struggling to enforce defensible space is also one of the hardest hit by wildfires in recent years: Lake County, just north of the Bay Area.

The Cal Fire unit that covers Lake County inspected just 12% of properties in its overall region in 2018. Local fire departments have also tried to do inspections, but have been busy with the catastrophic fires of recent years.

In 2015, the Valley Fire burned almost 2,000 homes and structures in the county. Then came the Clayton Fire in 2016, the Sulphur Fire in 2017 and the Mendocino Complex in 2018. That four-county blaze was the largest in state history, scorching 717 square miles, a bigger area than is taken up by the cities of Houston or Phoenix.

“We’ve burned up about 45 percent of our county land mass,” said Willie Sapeta, fire chief for the Lake County Fire Protection District. “Lake County as a whole is suffering from PTSD just because everyone is so traumatized by it.”

Sapeta has seen first-hand the difference that maintaining defensible space can make. In 2015, the Clayton Fire was racing through tall grass and brush on the outskirts of the town of Lower Lake. But it slowed down when it approached the Lower Lake Historic Schoolhouse Museum; there, the grasses had been mowed within 100 feet of the wooden building, creating a buffer. The shrubs around the museum also had large gaps between them, another important defensible space tactic.

The museum, and the buildings behind it, were left untouched by the fire.

“Definitely a big part of Lower Lake was saved by having that defensible space in place,” Sapeta said.

Today, the hills remain covered with dead, blackened trees, but the undergrowth has sprung back, fed by this winter’s abundant rain.

Even with the scars of wildfire still visible, Sapeta says, many homeowners still haven’t cleared their defensible space.

“Life happens,” he said. “They’ve got kids. They’ve got jobs. And then all of a sudden they don’t realize we’re in June and all that brush is right up against their home.”

The firefighters in Sapeta’s fire district, one of several covering the county, try to make defensible space inspections when they can. But mostly they’re responding to emergency calls like fires, car crashes and heart attacks.

To really educate homeowners and enforce the rules, Sapeta says, he needs dedicated inspectors.

“I would love to have a fire prevention program where I’ve got a staff of six or eight people,” he said. “Nothing more in the world I’d love, to be able to do that.”

He says the funds, however, aren’t there. “It takes everything we have just to keep our doors open. The small rural counties just don’t have the resources.”

Lake County’s Board of Supervisors passed its first defensible space ordinance earlier this year, despite the opposition of some members of the public concerned about the cost of clearing their properties.

Now, even without additional funding, inspectors are visiting homes for the first time. To do that, the planning department is temporarily pulling building inspectors off their jobs to focus on vegetation.

“Other counties are in the same boat, particularly like Butte and Shasta counties,” said Mary Jane Montana, Lake County’s chief building official. “None of us have a lot money, and we’re faced with the same thing. So, we kind of just had to say, ‘We’re doing it this year.’ ”

‘Everybody Wants to Save Their Community’

Fire safety is very different in other parts of California.

“All these homes have chimneys,” said Charles Butler, code enforcement officer for San Diego Fire-Rescue, squinting at a row of suburban homes. “Another thing I look for is tree canopy up over the chimney. That is a violation.”

Butler enters the information on an iPad, something he does at thousands of homes every year. He’s one of five inspectors responsible for about 45,000 homes in San Diego’s wildland-urban interface, where houses are nestled against open space or rugged canyons.

When he finds dead brush or tall weeds, he leaves the homeowner a notice about what to fix, with several weeks to comply. The city then does another inspection, and if the work still isn’t complete, follows up a third time.

If problems persist, the city hires a contractor to clear the brush. The owner is then on the hook for the cost, and a lien is put on their property. The city has to resort to this process, called “forced abatement,” on a few dozen properties each year, often at considerable cost to the owner.

Most people who don’t follow the rules are elderly or financially burdened, says Marcy Garcia, San Diego Fire-Rescue’s code compliance supervisor. In those cases, the city tries to connect violators with local fire-safe councils, the community-led groups that have grants or have other resources available to help get the work done.

Garcia says the overall compliance rate is high because the city provides crucial reminders to homeowners who may care about fire safety but haven’t gotten around to fixing their property.

“Especially in the areas where there have been fires before, they’re very receptive to it,” said Garcia. “Everybody wants to save their community.”

Cal Fire Struggling

In addition to local governments, Cal Fire is also responsible for enforcing defensible space regulations, for more than 750,000 homes and buildings within 31 million acres that fall outside city and town limits.

But across that territory, Cal Fire is struggling to meet its inspection goals, especially in rural Northern California.

A defensible space law, passed in 2005, requires a 100-foot buffer around homes in fire zones. From zero to 30 feet, homeowners must create a “lean and green” zone by trimming trees so they don’t hang over roofs and clearing dead grass and brush. Between 30 and 100 feet, they must keep shrubs spaced apart and grasses mowed to 4 inches or less.

“Our goal is to inspect every property in our responsibility area every three years,” said Steven Hawks, deputy chief for Cal Fire’s wildland fire-prevention engineering program. “Defensible space is a critical component to a home surviving a wildland fire.”

Cal Fire reports it’s close to its goal. From July 2017 through June 2018, it completed 217,666 inspections.

But doesn’t mean Cal Fire visited 217,666 properties.

A KQED analysis of almost a half- million inspection records shows the agency’s inspection rate was just 17% of properties in 2018, far below the agency’s 33% goal.

One reason for the discrepancy is that Cal Fire includes multiple trips to the same properties that failed a first inspection.

It also includes visits in areas where responsibility for inspections has been handed to county fire departments. And those rates are dramatically higher than Cal Fire’s.

The Orange County and Ventura County fire departments each inspect 100% of properties in risky fire zones every year. The Los Angeles County and Santa Barbara County fire departments get to around 60%.

While Cal Fire sends money to those counties, as well as Marin and Kern, because they do their own firefighting, it generally doesn’t cover the costs of their entire defensible space programs.

Achieving those high inspection rates takes substantial county investment. Some county fire departments have dedicated teams of year-round inspectors, while others rely on firefighting engine crews.

“It does take resources and commitment, but we do it because it’s one of the most important programs in the department,” says Ventura County Fire Marshal Massoud Araghi. “This is what we believe will save structures and will help our firefighters be safe.”

Araghi estimated a 99.9% compliance rate from the county’s homeowners, something he attributes to annual inspections.

“It’s very important the time period is consistent,” he said. “Everyone knows they have to have it clean by a certain time. If you have long periods of time in between, you won’t be successful.”

Resources Lacking

In some high-risk fire areas where Cal Fire does inspections, properties receive dramatically few inspections.

At the low end, just 6% of properties received inspections in 2018 by the Cal Fire unit that covers the Sierra Nevada counties of Amador, El Dorado, Sacramento and Alpine. At that rate, which has remained mostly consistent since 2010, each property would be visited about once every 16 years.

The same pattern is found in the nearby rural counties of Nevada, Yuba, Placer, Sierra and Sutter, where 7% of properties were inspected in 2018.

Even in Sonoma, Napa and Lake counties, where recent fires have been historically devastating, Cal Fire inspected just 12% of properties last year.

Cal Fire gives several reasons for the low numbers.

Every year, the agency hires between four and six defensible space inspectors in each of its 21 units throughout the state, but those inspectors are only funded to work three months.

Beginning in 2011, that money came from a $152 annual fee on homeowners within Cal Fire’s jurisdiction. But the levy was opposed by many in rural counties who saw it as an added tax, and in 2017, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill to suspend it.

Since then, Cal Fire’s defensible space funding has come from revenue generated by the state’s cap-and-trade program, designed to lower carbon emissions.

Without more funding, Cal Fire Deputy Chief Hawks says, it will be tough to increase the inspection rate.

Another issue is that inspectors are not distributed in proportion to the number of properties in each region. A Cal Fire unit that covers 35,000 properties has four seasonal inspectors, for example, but one with double that number has just six.

“We should look at the numbers like you’re looking at them,” Hawks told KQED. “We may have some units that have a larger number of parcels than others, and they should get more of the resources.”

Cal Fire has the power to hire contractors to clean up properties when homeowners don’t comply, but it’s not something the agency currently does.

“We don’t really have the staff to accomplish that mission,” Hawks said.

In general, Hawks says, Cal Fire hasn’t been able to hire enough people to take care of its defensible space responsibilities.

“We have not been able to fill our defensible space inspectors in every unit every year,” he said. “So having enough qualified people on the list to fill our positions is important.” Hawks could not provide numbers for how many positions have gone unfilled or the reasons why.

Typically, some inspections are done by the agency’s firefighters during down times. But with fire seasons getting longer and more intense, there hasn’t been much of that in recent years.

“It’s difficult with the fire seasons being the way they’ve been,” Hawks said.

Doubling Inspections

Lawmakers in Sacramento are now considering a bill, AB 1516, that mandates Cal Fire do inspections at a rate double what it does now. The bill requires the agency to inspect properties once every three years, beginning in 2021.

“We have to change the way that we think about clearing the foliage off of private property,” said the bill’s sponsor, Assemblymember Laura Friedman, D-Glendale. “Having one property that’s badly out of compliance can put an entire neighborhood at risk.”

The bill would also create new defensible space rules specifically for the zone within five feet of a building, something many defensible space experts recommend. Cal Fire would be responsible for identifying which kinds of plants homeowners aren’t allowed to grow in that zone.

“I would say absolutely the zero-to-5 feet is the most important place to focus on,” said Alexandra Syphard, chief scientist at Sage Underwriters, a company that evaluates the fire risk of homes for the insurance industry. “The things that tend to be the most important are those things that are right up against the house: trees overhanging your roof, vegetation that’s touching the structure.”

Many homes are ignited by embers that are blown ahead of a wildfire as opposed to actually being lit by flames. If a tree or bush next to a house catches fire that way, it can spread to the house.

Defensible space can reduce that risk and also give firefighters the necessary space to maneuver and defend a home.

“It doesn’t have to be drastic,” said Syphard. “You can still have a lot of vegetation on your property, but reducing it by at least 20% is a critical threshold where you do significantly improve survival chances.”

Still, she cautions that there’s no guarantee a home will be spared.

“A lot of homes with more defensible space than is even required are still destroyed by fires.”

With many Californians struggling to get fire insurance policies, there’s also a push for insurance companies to consider the maintenance of defensible space when setting rates.

“We have to look at how do we allow Californians to get maybe a discount for mitigating wildfire risk, for hardening their home … similar to what we give in terms of discounts for good drivers,” said Ricardo Lara, California’s insurance commissioner. “We’re pushing insurance companies now, and surprisingly they’re coming to the table.”

Cal Fire has not said what doubling inspections would cost, but if AB 1516 passes, the agency would request the funding as part of its annual budget.

“We do need more resources for Cal Fire,” said Assemblymember Friedman. “I do believe that Governor Newsom is very serious about investing to make our communities more resilient to fire and he’ll see the wisdom in investing in these kinds of programs.”