Somehow, Parker not only successfully survived all the trauma and hardship of her earlier life, she was also able to channel the pain and weight of those experiences into words that were as unflinching as they were vulnerable.

Parker came out as a lesbian in the late 1960s, having divorced her second husband, fellow writer Robert F. Parker. The liberation she felt finally embracing her sexuality is palpable in her poetry. Pat Parker knew no limits when it came to expressing the innermost parts of herself. The boldness of "My Lover is a Woman"—which uses an interracial lesbian relationship as a jumping-off point to talk about racism, poverty, and the prejudice faced by the LGBT community—is still astonishing in 2018. In 1968, hearing it for the first time must have felt like an earthquake.

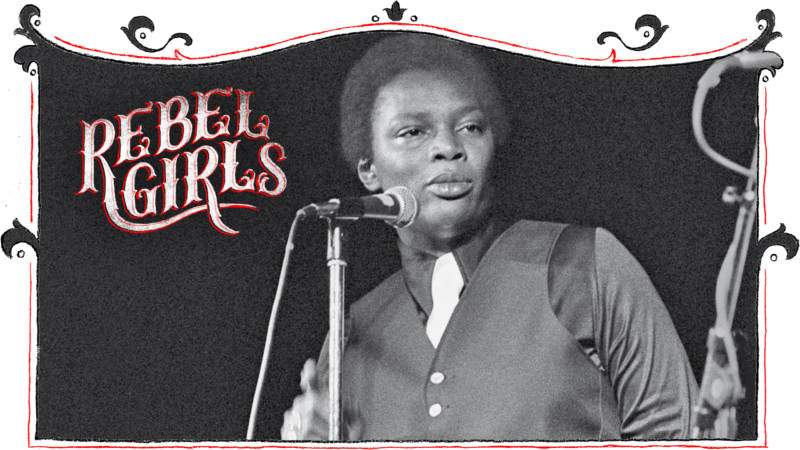

Parker was outspoken by nature, but found herself even more emboldened by her community. Alongside fellow lesbian feminist poets including Judy Grahn, she helped organize regular group poetry readings up and down the West Coast. Parker once said of this crew of innovators: “It was like, pioneering. We were talking to women about women, and, at the same time, letting women know that the experiences they were having were shared by other people.”

Parker's activism was at the center of almost everything she did. In addition to her work with lesbian and feminist groups, as well as her early involvement with the Black Panther Party, she formed the Black Women's Revolutionary Council in 1980, and assisted in the founding of the Women's Press Collective. In 1985, she worked with the United Nations, traveling with delegations to both Kenya and Ghana, before testifying before the U.N. about the status of women in the world.

It should come as no surprise that Parker's day job was as the director of Oakland Feminist Women's Health Center. She worked there for a decade, resigning only when terminal illness forced her to in 1988. Parker died in Oakland after a battle with breast cancer, on June 19, 1989 at the age of 45. She was survived by her partner of nine years, Martha "Marty" Dunham, and her daughters Cassidy Brown and Anastasia Jean Dunham-Parker-Brady. It was her children that inspired Parker's poem, "Legacy (for Anastasia Jean)"—a powerful critique of homophobic ideals around parenting.

There are those who think

or perhaps don’t think

that children and lesbians

together can’t make a family

that we create an extension

of perversion.

They think

or perhaps don’t think

that we have different relationships

with our children

that instead of getting up

in the middle of night

for a 2AM and 6AM feeding

we rise up and chant

“you’re gonna be a dyke

You’re gonna be a dyke.”

That we feed our children

Lavender Similac

and by breathing our air

the children’s genitals distort

and they become hermaphrodites.

They ask

“What will you say to them

What will you teach them?”

Child

That would be mine

I bring you my world

and bid it be yours.

Outside of her writing, Parker's legacy lives on in The Pat Parker/Vito Russo Center Library in New York City, as well as the Pat Parker Poetry Award for black, lesbian, feminist poets. More than that though, her outspoken activism lives on in those that have followed in her footsteps and in the forward strides made in civil and gay rights since her life ended.

After Pat Parker's devastatingly premature death, her lifelong friend Judy Grahn described the way Parker lived life and overcame challenges, as "go[ing] to the front of the line with a big bad sword in hand and lead[ing] a revolution." That, she most certainly did.

For stories on other Rebel Girls from Bay Area History, click here.