For several years now on Nov. 18, Robert Spencer has visited the Jonestown Memorial at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland. He plans to go again this month — on the 40th anniversary of the massacre that took more than 900 lives.

Robert didn’t personally know anyone who died in the mass killing in 1978, but he was connected. And that connection and where it would lead became his life’s mission in recent years.

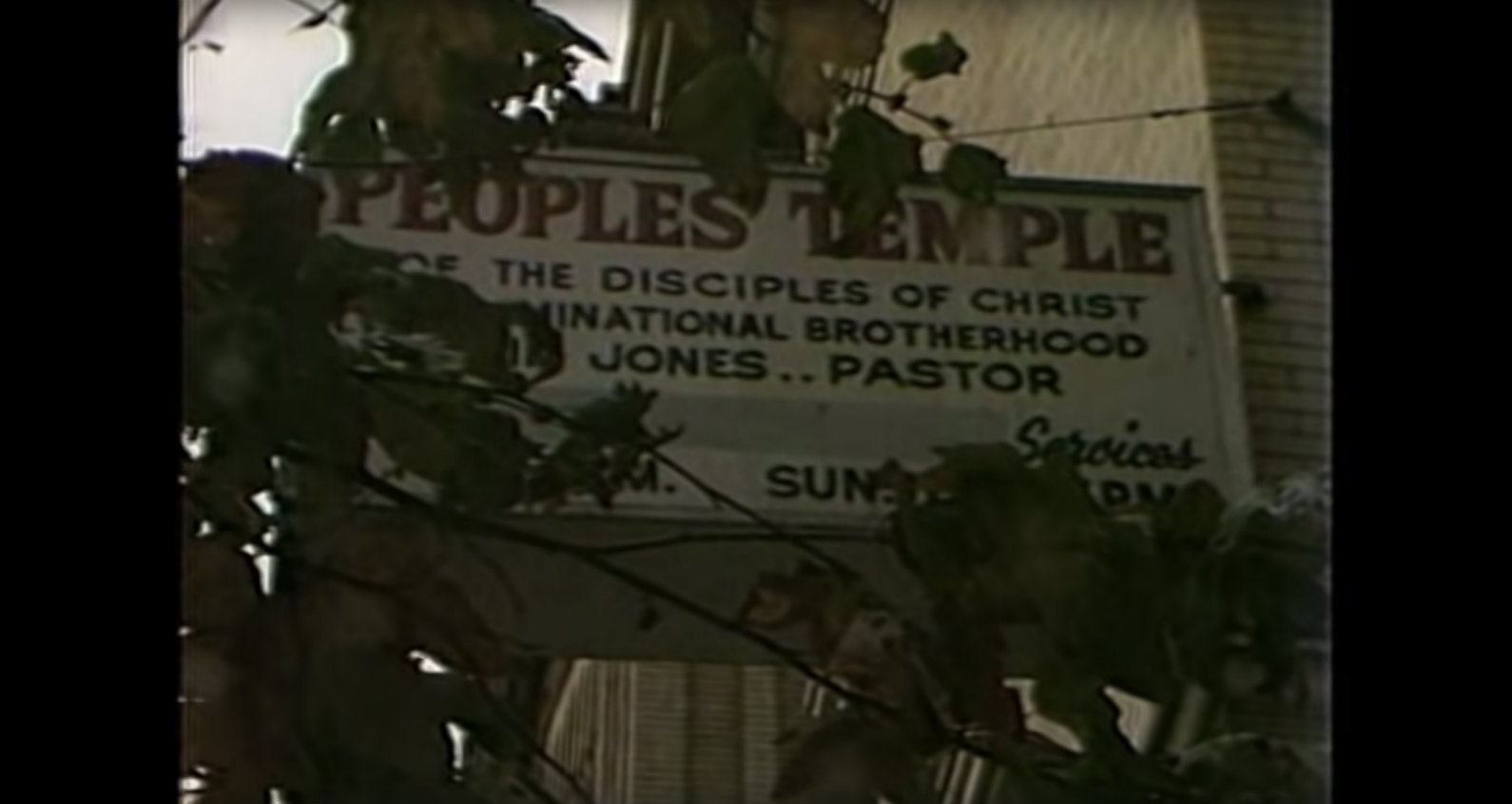

Most of the men, women and children who perished at Jonestown were from the San Francisco Bay Area. They were members of the Peoples Temple, led by Jim Jones, a charismatic white man who preached racial equality and socialism.

The Temple was headquartered in San Francisco, but Jones had come under increased scrutiny by the media there. In 1977 he pulled up stakes and took his followers to the South American jungles of Guyana, a multiracial country where he planned to build what he called a "rainbow utopia."

But Jones, a master manipulator, had become increasingly paranoid and unhinged.

The day of the massacre, some Temple members ambushed California congressman Leo Ryan, who had gone to Guyana to investigate the group and whether some followers were being held against their will.

Ryan -- along with three members of the news media and one Jonestown defector -- were killed. Rep. Jackie Speier, then an aide to Ryan, was shot five times.

That same day, Jones orchestrated what he called an act of “revolutionary suicide,” ordering his followers to drink cyanide-laced punch.

Back in the Bay Area, as this tragedy was still unfolding on the television news, Robert’s adoptive parents in Hayward told him his birth mother was among the dead. He was just 10 years old.

His birth mother’s name was Agnes Bishop Jones, and she was the eldest adopted child of Jim Jones and his wife, Marceline.

And if that wasn’t enough to lay on a kid, it turned out Agnes also had four other children, all of whom died with their mom in Jonestown.

Sitting in his home in Martinez, California, Robert still chokes up looking back at that time and the family he never knew. “The news is they’re dead. You’ll never see them. That was the end of that family line.”

Robert is 50 years old. He’s a park ranger in the San Francisco Bay Area, and a firefighter in the summer. He also volunteers at his church and labor union. He’s a helper -- the kind of guy who will go out of his way to change a stranger’s flat tire. “Maybe that's just a family trait, being helpful,” Robert wonders.

For years, Robert shut the door on his family connection to Jonestown and got on with his life. But as his own children were growing up, he became consumed by questions about why he’s helpful, why he’s tall, why his skin is olive and why his eyes are clear-blue.

He didn’t want to replace his adoptive parents, who he says loved and raised him. But he says there was “something about that biological connection” that he was desperate to experience.

He wanted to know more about his mother, Agnes, and about her life in the Temple. One big question that nagged him: Why wasn’t he with her and his siblings on that fateful day?

"I knew she was dead and I was just trying to connect with someone to say, 'Hey, not all was lost in 1978. You know, I made it at least.' "

Blood is a strange thing. It’s thicker than water for some people and totally overrated for others. The fact that both Agnes and Robert were adopted made searching for blood relatives that much harder, “Who’s family and who’s not?" he asks.

He knew from the internet some basic facts: Agnes was the oldest of eight children adopted by the Joneses. She was married three times. She was 25 years old when she had Robert and 35 years old when she died.

Then, a few years ago, Robert reached out to someone as close to Jonestown as he could get: the only biological child of Jim and Marceline Jones.

His name is Stephan Jones. He’s a tall, thin man with intense green eyes.

Stephan survived the 1978 tragedy because he was on the other side of the small South American country playing basketball when his father’s suicide order came down.

He was 19 years old at the time and had spent his entire life in the Temple.

In an interview in San Rafael, Stephan, now 59 years old, explains that even though Agnes was technically his sister, he didn’t really know her. She was 16 years older. “I don’t remember ever living under the same roof,” Stephan says.

Stephan does recall that Agnes didn’t spend a lot of time with her children in the Temple. That could be because the Temple was based on a communal model and the family unit was discouraged. Stephan also notes the “family” was seen as a "threat" to his father Jim Jones’ authority.

When Robert first emailed Stephan looking for information about Agnes, Stephan thought Robert’s story was plausible. He told him that Agnes came and left the Temple more than anybody he can remember. In retrospect, Stephan says her comings and goings were highly unusual.

“It’s a tragic irony that they all died down there, 'cause I never really felt she was part of the Temple,” says Stephan.

Virtually everyone in Jonestown died that day, including Stephan’s parents, one of his brothers, and Agnes, whom he remembers as a “lovely woman ... with a Southern-Midwestern twang.”

Stephan wanted to help Robert, in part because he feels an “obligation to be helpful when things connect to my history and my family.” But Stephan can also be wary of people wanting to make some connection to the Temple and Jonestown. People might be looking for a sense of belonging or perhaps trying to heal some deep trauma of their own.

When asked if he thought it strange for Robert to show up out of the blue claiming to be Agnes’ son, Stephan howls with laughter:

“You got to remember where I come from. Nothing seems strange as far as human behavior."

The two finally met in person in 2014 at a reunion of Jonestown survivors, friends and families in San Diego.

People there began asking questions about Robert’s claim that Agnes had put him up for adoption. They believed him, but it raised a red flag because Temple members didn’t put their children up for adoption to outsiders.

Stephan says some at the reunion began to speculate that perhaps Jim Jones was Robert’s biological father and he just wanted to “make that go away" by putting him up for adoption.

Some also commented that Stephan and Robert kind of looked alike. They were both thin at the time, they had a similar skin tone, and they had intense eyes.

Robert also began wondering if Jim Jones might be his biological father and asked Stephan if he would take a DNA test.

But the idea that Jim Jones might be Robert’s father is pretty creepy on a few levels. For one thing, it would mean Agnes might have been molested by her adoptive father.

The genetic test raised a big question for Robert -- one that Stephan asked him point-blank: “Do you really want to know that Jim Jones is your dad? Do you want to know that?”

Stephan was also concerned that Robert might be looking for a family connection that he couldn’t necessarily provide. Stephan was raised in the Temple and thrown together with eight adopted siblings of different backgrounds. He had no history with Robert and told him that if they did share the same father, it “changes nothing for me.”

Despite his concerns, Stephan didn’t want to be the one person standing in the way of something so important to Robert. And so Stephan agreed to take the DNA test.

It took a long time to get the result, but there was a sense of relief for Robert when it came back negative. “That would have been horrible news to find out that Jim Jones is your father,” he says.

For Stephan, the actual biological son of Jim Jones, the DNA test was an end in itself. He moved on. He had his own family to think about.

Robert admits there was a slight disappointment with the test result. “Man, I thought I may have got a brother, and that was not the case after all.”

Robert was incredibly frustrated. He’d been searching off and on for a decade for a living blood relative.

But over the next few years, he kept up the search. While he was working his day job as a park ranger near Oakland, and fighting wildfires around the state, he was sending off his DNA to various websites.

Robert’s luck was about to turn.

This past summer, as he was running between blazes, he found a genetic match with a man named Harmony LaBeff, a 37-year-old pastor in Chicago. The two couldn’t quite figure out how they might be related.

At this stage, Robert also had a DNA match with a distant cousin, who was a whiz at genealogy.

After a lot of online sleuthing, she thought she had found a close relative of Robert's. Not of his birth mother, Agnes, but the man who crossed paths with her back in 1967.

Harmony LaBeff’s grandfather, Thomas LaBeff, was born in Smackover, Arkansas, in 1935. He now lives in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

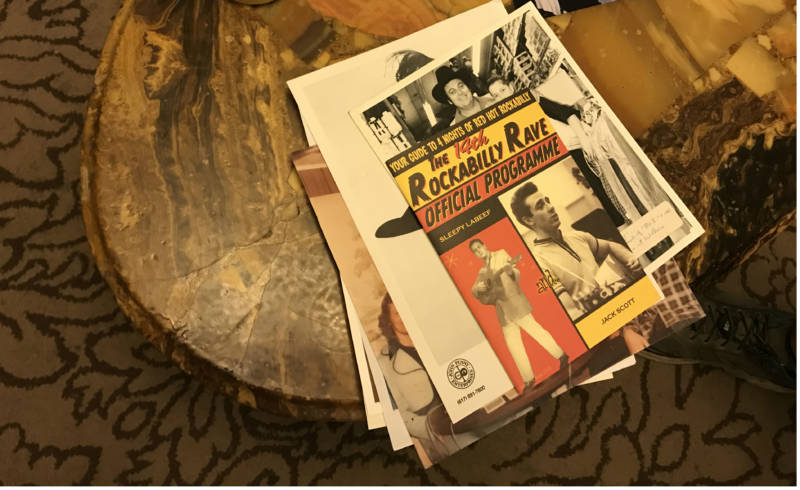

Most people don't know Thomas by his birth name. Columbia Records changed it when he began performing decades ago. Sleepy LaBeef’s numerous album covers feature a tall man with slightly sleepy eyes, which is where he got his first name "because I looked like I was about half-awake most of the time," he explains with a chuckle.

Sleepy LaBeef has been playing a rich mix of American roots music -- blues, country and rockabilly -- for more than six decades. At 83 years old, he still commands a stage with his rich baritone and guitar playing. In fact, he’s got a concert lined up in Ohio in December.

Sleepy is considered a musical icon to his fans, many of whom say he never quite got the recognition he deserved.

That may be one reason Robert had never heard of Sleepy prior to getting the DNA match with Sleepy’s grandson. Sleepy and his family had never heard of Robert, until this past August when he left a phone message saying he might be related to Sleepy. Sleepy’s wife, Linda, says she “didn’t give it a high priority," assuming it was a distant cousin of Sleepy's.

Since Robert was not getting a return phone call, he put his firefighting duties aside, and jumped on a plane to Fayetteville for the ultimate cold call.

Upon landing, Robert called Sleepy again and the two agreed to meet at a coffee shop. Robert, not knowing what to expect, arrived early and asked for a more private table.

But it turned out it wasn’t just Sleepy coming. His whole family arrived: his wife, their kids and their grandchildren.

Linda says she picked Robert out instantly at the restaurant because of his strong physical resemblance to Sleepy.

Robert’s eyes and smile were the giveaway for Jesse, Linda and Sleepy’s oldest daughter. “He pretty much looks like a younger version of my dad," she says.

Robert didn’t see the resemblance. Of course, he was staring across the table at an 83-year-old man. But from the moment they all met, they describe an instant connection, almost spiritual. “He was family,” says Linda.

The two decided to take a DNA test to confirm they were related. But Linda describes their bond as so strong with Robert that even if there was no DNA match, they’d still want him as part of their family. Yet everyone agreed a test was still needed, if only to give Robert a sense of validation.

Robert and Sleepy went to a lab in Fayetteville and took the test. Robert didn’t get the result until he returned to California: 99.99 percent probability that Sleepy is Robert’s biological father.

Robert had yet to really raise the subject of Agnes with Sleepy. The DNA confirmation gave him hope that his father could provide some insights into his birth mother.

Within three weeks, Robert jumped on a plane again for a 10-day visit to Arkansas. He threw himself into the family’s daily routine, helping shuttle grandkids to various activities.

In the evening, he’d bend over photo albums tracking the family and Sleepy’s musical life on the road, trying to digest decades of lost history.

At this early stage in their relationship, Robert had already begun calling Sleepy and Linda "Dad" and "Mom." The three daughters are calling him their brother.

It’s hard not to be struck by how fast the new relationship is moving. They have no shared memories, holidays or dramas—all the wonderful and messy stuff that defines family for so many.

Sleepy, who has a large family of half-siblings, says he’s not surprised things are working out. “There’s always room for more,” he chuckles.

Robert had finally found the family he’d been searching for, and along the way he also found some answers: His olive skin is from his mother and his tall build and blue eyes are from his dad.

But Sleepy couldn't provide any insights into Agnes. The details of how Sleepy met his birth mother back in the 1960s are pretty fuzzy. Sleepy says he likely met Agnes at a Nashville club, possibly Tootsie's Orchid Lounge or the Honey Club. Fans would come backstage to meet the musicians and “sometimes we were not as responsible as we should have been ... and so things happened,” says Sleepy.

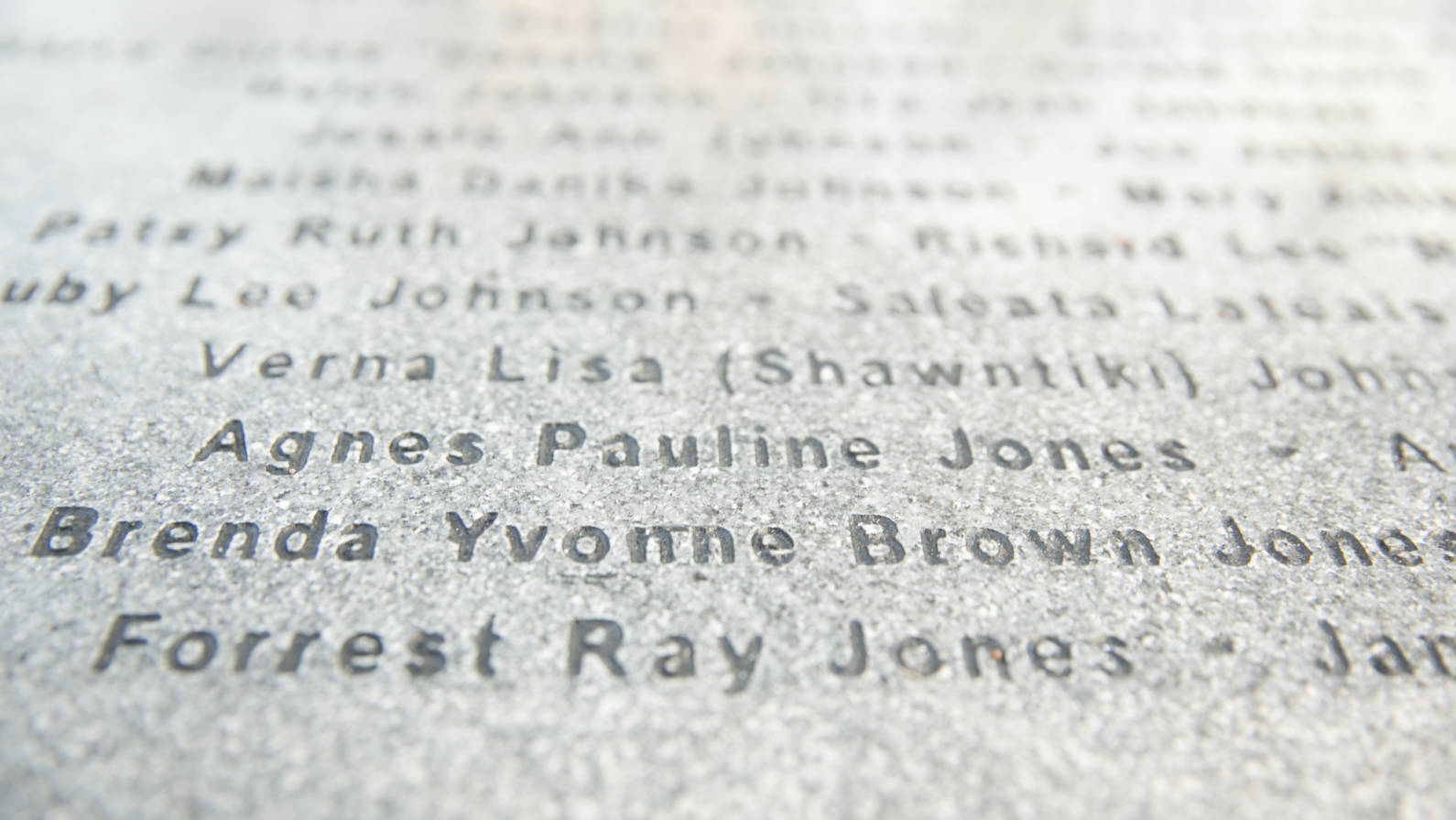

About 10 years after things "happened" between Sleepy and Agnes, she and her four children would die in Jonestown. Her body was buried in Indiana, where she was born. The unclaimed bodies of her children -- Robert’s siblings -- were placed in a mass grave in Oakland.

Just four days before the tragedy, Sleepy and Linda got married in Texas. They watched the news in horror with the rest of the country.

“And Robert escaped that,” says Sleepy. “So that was a blessing that he missed it.”

So many things Robert has wanted to know about his birth mother are buried in Jonestown. But he seems at peace, concluding he's a product of the times: a "rock 'n' roll baby.”

Some families are joined at the hip and some try desperately to get away from each other. Robert Spencer sought out complete strangers and got lucky with a DNA match and acceptance. But even his new Arkansas family will require some navigating. “I'm a Democrat, they're Republicans. And so we're different.”

Robert doesn’t seem concerned about this red-blue divide. Or that they’re Pentecostal and he’s not.

He is already planning to return to Fayetteville for Thanksgiving, when the extended family is set to welcome him and his family into the fold.

Robert says it will be a fitting holiday since he has so much to be thankful for: his adoptive parents for raising him in a loving home, for Stephan Jones for helping him in his long search, and for his new family in Arkansas for embracing him so unconditionally.

And, of course, he's thankful for Agnes for giving birth to him in the first place, and then letting him go.